Commentary

(pdf)Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Großmann’s advertisements for musical entr’actes

3. Jakobi and Berner

4. The identity of the violin concerto

5. Magdalena Viktoria Schroth

Introduction

(⇧)Few performances of Mozart’s violin concertos are documented during his lifetime. The composer is known to have played a violin concerto at the consecration of the pilgrimage church of Maria Plain in Salzburg on 19 Aug 1774 (Neue Folge, 25); if the concerto was one of his own, it must have been K. 207 in B-flat, the only violin concerto he had composed by that point. He also performed a violin concerto for his sister’s name day on 25 Jul 1777 (Dokumente, 144), and played his “strassbourger=Concert” (K. 216) at the Holy Cross Monastery in Augsburg on 19 Oct 1777 (Briefe, ii:82). Up to now, only two other violinists had been known ever to have performed a Mozart violin concerto during his lifetime: a Herr Kolb, whose identity is uncertain, and Antonio Brunetti, a violinist at the Salzburg court. In Salzburg, Leopold Mozart heard Kolb perform a violin concerto by Wolfgang on 26 Sep 1777 at the Eisenbergerhof (Briefe, ii:18), and on 9 Jul 1778, Kolb performed one in front of the house of Joachim Rupert Mayr von Mayrn (Briefe, ii:436). (Kolb also played a violin concerto at the Mozart residence on 15 Aug 1777, but it is unclear whether that concerto was by Mozart; see Dokumente, 145). Brunetti performed works by Mozart for violin and orchestra on at least two occasions. On 4 Oct 1777, Leopold heard Brunetti play K. 216 at the theater in Salzburg (Briefe, ii:36); and in a letter to his father, Mozart mentions that Brunetti performed his newly composed Rondeau, K. 373, in Vienna on 8 Apr 1781 (Briefe, iii:103; see also our entry for 23 Mar 1781).

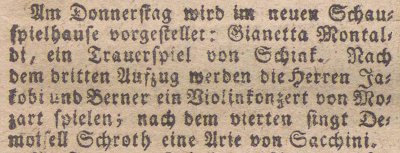

The advertisement transcribed above, for a performance in Frankfurt by the theatrical company of Gustav Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann, adds two new names to the list of those known to have performed a Mozart violin concerto during his lifetime: Jakobi and Berner. The Frankfurt advertisement is currently the only known reference to a performance of a Mozart violin concerto by someone outside the composer’s circle during his lifetime.

Großmann’s advertisements for musical entr’actes

(⇧)Großmann’s theatrical company began performing in Frankfurt am Main in 1780. The company had been in residence in Bonn since 1778, and in order to maintain performances in overlapping seasons in the two cities, Großmann split his company in Oct 1782, with Großmann himself directing the portion in Frankfurt and his wife Karoline the one in Bonn. The residency in Bonn was cut short in the spring of 1784 by Karoline’s death and that of elector Maximilian Friedrich (on Großmann’s Bonn residency, see our entry for 2 Aug 1783). In the autumn of 1784, Großmann reassembled his company in Frankfurt to perform at the recently built Komödienhaus during the city’s trade fair (“Herbstmesse”; on the Komödienhaus see our entry for 2 Aug 1783). The company’s season apparently began on 30 Aug (for a detailed discussion of the season’s starting date, see the Notes below).

During September, the company performed Mozart’s music on several occasions. On 8 Sep 1784, Großmann programmed Die Entführung aus dem Serail, which the company had first performed in Frankfurt the previous year (see our entry for 2 Aug 1783). In September, Aloisia Lange, Mozart’s sister-in-law, and her husband Joseph Lange visited Frankfurt, and both made several guest appearances with Großmann’s company. Aloisia appeared as Konstanze in Entführung on 29 Sep, and perhaps also on 8 Sep. (For a detailed schedule of the Langes’ appearances in Frankfurt, see our entry for 29 Sep 1784.) Mozart’s violin concerto was advertised as an entr’acte on 16 Sep during Gianetta Montaldi, a tragedy by Johann Friedrich Schink which premiered on 24 Nov 1775 in Hamburg.

Großmann regularly advertised his upcoming performances in the Frankfurter Staats-Ristretto, also noting the performance of musical entr’actes—vocal pieces or instrumental works performed between the acts of plays and singspiels. In total, Großmann advertised twelve musical entr’actes in 1783 and 1784.

Musical entr’actes advertised by Großmann in the Frankfurter Staats-Ristretto in the years 1783–1784

| Day | Work | Genre | Entr'acte |

|---|---|---|---|

Lanassa (Plümicke) |

Trauerspiel |

“Zwischen den Aufzügen wird Herr Jakobi Konzert auf der Alt=Viole geben.” |

|

Die Vormünder (Schletter) |

Lustspiel |

“Zwischen den Aufzügen werden Italienische Arien gesungen.” |

|

Der argwöhnische Liebhaber (Bretzner) |

Lustspiel |

“Zwischen den Akten wird eine neue Sängerin einige Arien von den besten Komponisten singen.” |

|

Die beyden Billets (Wall) |

Lustspiel |

“Zwischen den Akten wird Herr Jakobi Concert auf der Violine spielen.” (The entr’acte was performed between the acts of Grétry’s singspiel.) |

|

Der verdächtige Freund (Leonhardi) |

Lustspiel |

“Zwischen den Aufzügen werden einige Bravour=Arien von Demoiselle Schroth und Herrn Stengel gesungen werden.” |

|

Lanassa (Plümicke) |

Trauerspiel |

“Zwischen den Aufzügen und nach dem Stück werden Madam Petenkam [Beckenkam] und Herr Pfeifer einige Arien und ein Duett von Sales und Sanhini [recte, Sacchini] singen.” |

|

Alter hilft vor Thorheit nicht, oder: der junkerirende Philister (Mylius) |

Fastnachts-posse |

“Eine Fastnachtsposse in fünf Aufzügen nach Moliere von Mylius, mit musikalischen Zwischenspiel.” |

|

Das Testament (Schröder) |

Lustspiel |

“Zwischen den zweyten und dritten Aufzug wird Herr Jakobi ein Concert auf der Violin spielen.” |

|

Die eingebildeten Philosophen (Stephanie/Paisiello) |

Singspiel |

“Zwischen den Akten wird Herr Kronenburg, ein Virtuose von Maynz, ein Concert auf dem Violonschell spielen.” |

|

Die Glücksritter (Schlosser?) |

Lustspiel |

“…und ein Violin=Konzert von Jakobi.” |

|

Gianetta Montaldi (Schink) |

Trauerspiel |

“Nach dem dritten Aufzug werden die Herren Jakobi und Berner ein Violinkonzert von Mozart spielen; nach dem vierten singt Demoisell Schroth eine Arie von Sacchini.” |

|

Der Eheprokurator (Bretzner) |

Lustspiel |

“Auch werden die Herren Jakobi und Berner ein neues Konzert auf der Violin spielen.” |

Großmann programmed most entr'actes between the acts of spoken plays, but at least twice he scheduled one between the acts of a singspiel. The entr’actes were mostly either a selection of arias or an instrumental concerto with one or two soloists. The offerings on 16 Sep 1784 were an exception, including both an instrumental work and an aria. Mozart, Antonio Sacchini, and Pietro Pompeo Sales are the only composers specifically mentioned in Großmann’s advertisements of entr’actes. Sacchini and Sales appeared as composers of arias; Mozart is the only instrumental composer named. Because the company had performed Die Entführung aus dem Serail just ten days earlier, and because the Langes were visiting Frankfurt, Großmann might have thought the concerto complemented the offerings of that month.

Jakobi and Berner

(⇧)Jakobi and Berner performed “ein Violinkonzert von Mozart” (“a violin concerto by Mozart”), but because two performers are named, the identity of the work and their roles in the performance are unclear.

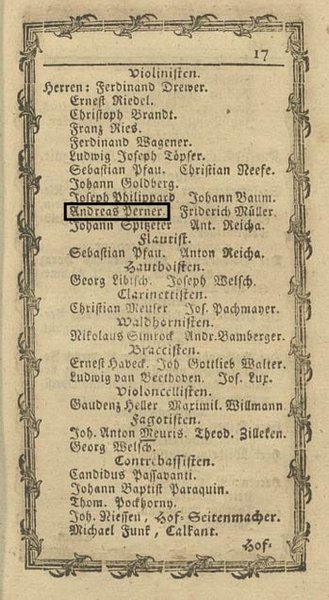

Jakobi and Berner were both proficient on the violin and keyboard, and both might occasionally have dabbled in composition (for sources on these two musicians and their first names, see the Notes below). Andreas (Andre) Berner (1766–1791) was born in Bohemia and played violin with Großmann’s company during the mid-1780s. After Großmann left Frankfurt at the end of 1786, Berner remained in the city until 1788, when he moved to Bonn. He spent his last years working alongside Christian Gottlob Neefe and Beethoven, and he died in Bonn in 1791.

A page from the Kurkölnischer Hofkalender auf das Jahr 1790,

showing “Andreas Perner” in the violin section of the court orchestra.

Beethoven appears twice in the list, as organist and violist.

Neefe appears as organist.

According to Gerber, Neefe held Berner in high esteem:

[…] [Berner] besaß nach Neefe's Urtheile, ein

ungemeines Kunsttalent, war ein vorzügli=

cher Orchestergeiger, der einen langen

und kräftigen Bogen führte, und im Solospie=

len große Schwierigkeiten besiegte.

[Gerber 1812, 359]

[…] [Berner] possessed, in Neefe’s judgement,

an exceptional artistic talent; he was an

excellent orchestral violinist who wielded

a long and powerful bow, and overcame

great difficulties in his solo playing.

Gerber’s description of Berner’s playing and character is adapted from an obituary published in the Musikalische Korrespondenz der teutschen Filarmonischen Gesellschaft für das Jahr 1791 (Wed, 31 Aug 1791, col. 279). Though the obituary is not signed, it may have been written by Neefe himself.

Jakobi (probably Conrad) was “Korrepetitor” (répétiteur, or vocal coach) and concertmaster for Großmann’s company between 1781 and 1785. When Großmann left Frankfurt for good in 1786, Jakobi remained in the area, serving at times as concertmaster, répétiteur, and violinist for the Nationaltheater in nearby Mainz until 1792, when the company disbanded as a result of the French occupation of the city. He served in the court orchestra in Mainz until 1794. That year, Jakobi visited Dessau and performed with the orchestra in the theater company of Friedrich Wilhelm Bossann; the two had previously worked together in Großmann’s company in 1785 (ThK 1786, 252). On 18 Sep 1794, Jakobi organized a “great vocal and instrumental concert” in Dessau (“ein großes Vocal- und Instrumental-Concert”) in which he played a violin concerto by Mozart, perhaps the same one that he had performed ten years earlier in Frankfurt (von Prosky 1884, 16). It is uncertain whether Jakobi remained in Dessau or returned to Mainz after his stint with Bossann. In either case, by 1797, he was again in Dessau, serving as musical co-director, with Neefe, of Bossann’s company (ThK 1798, 197). Jakobi remained in Dessau until his death on 21 Jun 1811 (AmZ xii: 34, col. 579, 21 Aug 1811; Gerber gives his date of death as 11 Jun 1811).

Gerber heard Jakobi play in 1785 and was impressed by the young violinist: “[Jakobi] ist auf der Violin ein eben so empfindungsvoller und fertiger Solospieler, als er bey seinem Orchester feuriger und einsichtsvoller Anführer ist” (“[Jakobi] is just as expressive and skilled a soloist on the violin, as he is a fiery and insightful leader with his orchestra” Gerber 1790, 681). It appears, given Gerber’s positive comments on both performers as well as their positions in court and theater orchestras, that either violinist would have been a competent soloist in a Mozart violin concerto.

The identity of the violin concerto

(⇧)Of Mozart’s five solo violin concertos, only three are plausible candidates to have been performed by Jakobi and Berner in Frankfurt in 1784: K. 207, K. 216, and K. 218. The other two—K. 211 and K. 219—do not appear to have circulated before the nineteenth century. An advertisement by music copyist Johann Traeg in the Wiener Zeitung on 16 May 1789 shows that K. 207 was in circulation during Mozart’s lifetime. Although the key of the concerto is not mentioned in the 1789 advertisement, Traeg’s 1799 catalog contains only one violin concerto by Mozart, in B-flat, which must have been K. 207 (Edge 2001, 798). A set of parts for that concerto in the hand of one of Johann Traeg’s copyists survives in Frankfurt (D-F, Mus. Hs. 2356). However, the paper-type of that set suggests that it was produced in Vienna between 1795 and 1800 (Edge 2001, 966); if that is correct, then it cannot be the set used by Jakobi and Berner in 1784.

Eighteenth-century parts also survive for both K. 216 (US-CAh, f MS Mus 204) and K. 218 (D-F, Mus. Hs. 2357). The paper-types of these sets appear not to have been in use before the mid-1790s, and the parts appear to be of German origin; they were probably produced around the time of Jakobi’s 1794 performance (Edge 2001, 1251 and 1255). The parts for K. 218 come from the estate of Heinrich Henkel, who inherited them from Johann Anton André, the music publisher who purchased Mozart’s estate from his widow in 1800 (Edge 2001, 1082ff and Plath 1970, 334ff). However, the paper-types and handwriting suggest that André acquired the parts for K. 218 in the mid-to-late 1790s, before he acquired Mozart’s estate (Edge 2001, 1255). The violin part for K. 216 is in the same hand as the parts for K. 218, and though its provenance is unclear, it likely also belonged to André, who probably acquired it around the same time he acquired the parts for K. 218.

We cannot confidently assert any connection between Jakobi, Berner, or Großmann and the surviving parts for any of these three concertos. However, given that K. 207, K. 216, and K. 218 are the only solo violin concertos by Mozart with demonstrable circulation outside of Salzburg and Vienna before the nineteenth century, they are probably the likeliest candidates for the 1784 entr’acte performance.

If Jakobi and Berner did in fact perform one of the concertos for solo violin, the advertisement is unclear about the performers’ roles. It is possible that two violinists are listed because they alternated movements as soloists. Otherwise, they may have performed a reduction with one man at the keyboard and the other on violin. In addition to being skilled violinists, Jakobi and Berner were also proficient at the keyboard. Jakobi, in his role of répétiteur, would have had to accompany singers regularly, while Berner would have likely developed keyboard skills while learning to compose. On a night when Großmann did not require his full orchestra to perform an opera, these two performers would still have been able to tackle a substantial instrumental concerto in keyboard reduction. Another possibility is that one of the violinists served as soloist while the other directed the orchestra, if one was present that night.

It is also possible, though less likely given the phrasing of the advertisement, that Jakobi and Berner did not perform a solo violin concerto, but instead one of Mozart’s concertos for two soloists. Gerber reports hearing Jakobi and Berner play a double concerto in 1785, only a year after their performance of the Mozart concerto:

Diese Gelegenheit war die nämliche […] wo ich

auch diesen Berner mit dem ersten Feuer der

Jugend 2 Konzerte von seiner Kompo=

sition spielen hörte; das eine allein, und das andere

ein Doppelkonzert mit H. Jacobi,

damaligen Vorspieler beym Großmanni=

schen Orchester. Es war bewundernswür=

dig, wie sich diese beyden jungen Künstler

um die Wette beeiferten, alle nur möglichen

Schwierigkeiten mit Ehren zu besiegen.

[Gerber 1790, 681]

This opportunity was the one […] during which

I also heard Berner play two concertos of

his own composition with the first fire of youth;

one of them alone, and the other a double-concerto

with Herr Jacobi, at the time concertmaster of

Großmann’s orchestra. It was admirable how

these two young artists strove to overcome all

possible difficulties with honor.

One might be tempted to think that on 16 Sep 1784, Jakobi and Berner performed Mozart’s only concerto for two violins: the Concertone for Two Violins and Orchestra, K. 190. Yet there is no evidence that the Concertone circulated during Mozart’s lifetime; its autograph is the only known source from the eighteenth century.

The Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364 is the only other plausible candidate. It might have been performed with Berner on the violin and Jakobi on the viola, since the latter is known to have played that instrument, at least occasionally (see Frankfurter Staats-Ristretto, 26 Apr 1783 and Theater-Journal für Deutschland 1784, 72). The Sinfonia Concertante seems to have circulated during Mozart’s lifetime, although perhaps not beyond Salzburg and Vienna. A set of parts now in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich is—with the exception of the violone—in the hands of Viennese copyists from Mozart’s time, and to judge by the paper-types, the set was probably copied in the early 1780s (D-Mbs, Mus. Mss. 6843; the part for violone is in the hand of Joseph Estlinger, a Salzburg copyist for the Mozart family; for a detailed analysis, see Edge 2001, 875; see also Eisen 1991, 306).

Finally, it is conceivable that Jakobi and Berner did not perform a concerto at all, but one of the movements with concertato violin from Mozart’s orchestral serenades. Parts for K. 203 survive in Graz (A-Gk, L 43), Modena (I-MOe, Ms. Mus. E. 158), and Brno (CZ-Bm, A 16.828); but none of these includes the movements with concertato violin (movements ii, iii, and iv). The Cassation K. 63 includes an adagio with concertato violin (movement v) with parts surviving in Lambach (A-LA, 40) and Kremsmünster (A-KR, H 21/87). Though these parts predate Jakobi and Berner’s performance, the circulation of K. 63 seems to have been limited to Salzburg and its neighboring areas (for a more detailed discussion, see the Notes below).

Magdalena Viktoria Schroth

(⇧)Großmann’s advertisement also states that an aria will be sung by “Mademoiselle Schroth”—Magdalena Viktoria Schroth. Schroth was born in Philippsburg am Rhein in 1763 and joined Großmann’s company sometime in the latter half of 1783 (Rüppel 2010, 294). She is first listed in the 1784 Theater-Kalender as “singing in the opera” (“singt in der Oper”) in Großmann’s company (ThK 1784, 320). She made her debut in Piccinni’s Das gute Mädchen (a German adaptation of La buona figliuola) as the Baroness (Marchesa Lucinda) probably on 26 Aug in Frankfurt (for a more detailed discussion of her debut date, see the Notes below). It is possible she was the “new singer” scheduled to perform “arias from the best composers” on 7 Aug 1783. After her debut, she sang some “Bravour-Arien” as an entr’acte on 9 Sep 1783.

Schroth moved to Bonn in the following weeks, joining Großmann’s company there and perhaps taking singing lessons with his wife, Karoline Großmann (in a letter to her husband from 4 Nov 1783, Karoline refers to Schroth as “unsere Schülerinn”). After Karoline's death and the dissolution of the Bonn troupe in 1784, Schroth traveled with Großmann’s eldest daughter and a few members of the company to Frankfurt (LTZ 3:30, 31 Jul 1784, 79).

In her early days, Schroth must have shown much promise as a singer, since she was initially cast in virtuosic roles, such as the Baroness in Das gute Mädchen. To perform this role, Schroth must have been capable of managing the extensive coloratura passages of arias like “Furie di donna irata.” The arias chosen for her entr’acte in Sep 1784 could have been similarly demanding. Schroth’s other known role that season was Laura in Georg Benda’s Romeo und Julie on 22 Feb 1784. Although that role is simpler vocally —it has one modest aria, a more challenging recitative and aria, and a duet—she did not fare well in the premiere (Friedrich Wilhelm Dengel to Großmann, 23 Feb 1784, transcribed here).

We do not currently know any of Schroth’s other roles in 1783–84, so it is difficult to provide a detailed vocal profile. Her next known role was in 1785, as a young shepherdess in a German adaptation of Beaumarchais’s Le Mariage de Figaro (Rüppel 2010, 306–7). The 1785 Theater-Kalender lists her in Großmann’s company as playing “Liebhaberinnen, junge Mädchen im Singspiel” (ThK 1785, 209).

We can only speculate what aria by Sacchini Schroth might have sung on 16 Sep 1784. During the season 1783–84, Großmann’s company performed only two operas by Sacchini, both in Frankfurt: L’Olimpiade, in a German adaptation as Die olympischen Spiele, and L’isola d’amore as Die Kolonie. The company performed Die olympischen Spiele on 16 Mar, 6 May and 7 Oct 1783. If Schroth debuted on 26 Aug 1783, she could not have sung in the first two of these performances. It is possible, however, that she performed in Frankfurt on 7 Oct. She could also have performed in Die Kolonie on 18 Oct, but if so, she would have missed the beginning of the Bonn season on 12 Oct. We know from Karoline’s letter that Schroth was in Bonn, at the latest, by 4 Nov.

If Schroth prepared a role for Die olympischen Spiele, it might have been either the prima donna Aristea or the seconda donna Argene. In Die Kolonie, she might have performed Belinde, the more serious role in the four-voice intermezzo. Though one would imagine that on the night of the Mozart concerto Schroth sang arias she had already prepared, it is certainly possible that she sang something else by Sacchini.

Schroth married Großmann sometime in the summer of 1785. Their marriage caused some controversy, as it was rumored that Schroth had had affairs with several men, among them Jakobi. Many of Großmann’s friends, including Neefe, cautioned him against marriage. (The details of their marriage are discussed in Rüppel 2010, 313–21). Großmann and Schroth remained married until Großmann’s death in 1796.