Commentary

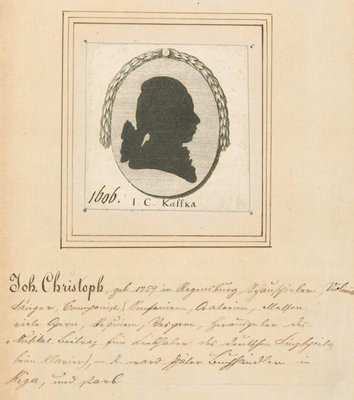

(pdf)Johann Christoph Kaffka (1754–1815), the author of the comedy Sechs Freyer und keine Braut (Six Suitors and No Bride, 1787), is a fascinating character, whose colorful biography, while not otherwise intersecting Mozart’s, is worth a digression.

Kaffka was by turns composer, librettist, prolific author (in a variety of genres), singing actor in a succession of itinerant theatrical companies, occasional theater director, bookseller, journal editor, and apparently a musical plagiarist. His activities were so diverse and his life so peripatetic that the basic facts of his biography are uncertain, varying from source to source. Gerber, in his Neues Lexikon (published while Kaffka was still alive), gives Kaffka’s birthdate as 1747, while noting that Kaffka himself claims to have been born in 1759. Some modern reference works state that “Kaffka” was a pseudonym for “Engelmann” (Gottzman & Hörner 2007) or perhaps the other way around (Grove Music Online); the idea that Kaffka’s “real” name was Engelmann is found in an early nineteenth-century dictionary of writers and intellectuals in the Baltic lands (Recke & Napiersky 1829), but there seems to be no clear direct evidence that Kaffka ever used the name.

In spite of the confusion, it seems relatively certain that Kaffka was born in Regensburg, probably in 1754 (the most frequently cited date), the son of Joseph Kaffka, a violinist in the orchestra of the Thurn und Taxis court. Johann’s older brother Wilhelm was an accomplished violinist who eventually became concertmaster of that same orchestra. According to Recke & Napiersky (1829), Kaffka’s parents intended him for the church, but he caught the theatrical bug at an early age while attending the Jesuit gymnasium, after playing the role of an angel in a procession (perhaps the ultimate source of the “Engelmann” story). Following the suppression of the Jesuit order in 1773, Kaffka entered the novitiate with the Cistercians in Kaiserheim; while there, he is said to have woven into his sermons passages from Lessing’s Emilia Galotti and other plays, perhaps foreshadowing his later habit of appropriating and adapting the work of others. He left the Cistercians before completing his novitiate, working briefly as a trainee in the Thurn und Taxis chancellery before taking up the position of music director in the German theater in Prague in 1775 (this according to Recke & Napiersky). He then led a wandering life for many years as actor, singer, and author with a variety of itinerant theatrical companies, working in Nuremberg, Frankfurt, Leipzig, Dresden, Prague, Brünn (Brno), and Breslau (Wrocław).

The Gallerie von Teutschen Schauspielern und Schauspielerinnen paints an unflattering picture of his capabilities as an actor and author, while noting that his appearance made him highly popular with his female audience:

Er hat alle äussere Eigenschaften eines Schauspielers; Figur, Bildung und Anstand, allein es fehlt ihm an Seele und Einsicht. Seine Sprache ist etwas unverständlich, aber nur weil er immer zu geschwind spricht. [...] An musikalischen Kentnissen fehlt es ihm wohl nicht, da er selbst Kompositeur ist, wenn schon nicht mit vielem Glük. Seine Stimme aber ist rauh, unangenem; sein Vortrag einförmig; Fertigkeit hat er gar nicht, und überhaupt kan er als Sänger nicht in Betracht kommen. Demungeachtet spielt er alle erste Rollen in der Operette, und gefällt fast aller Orten. Er kennt die Wirkung seiner äussern Eigenschaften, debütirt daher jederzeit als Deserteur in der Operette. Seine äusserst vortheilhafte Figur durch einen sehr vortheilhaftten Anzug in das schönste Licht gesezt, nimmt das ganze Auditorium und zumal die weibliche Hälfte desselben, gleich zu seinem Vortheile ein, und fast immer wird er gleich bei seinem ersten Auftritte, wenn er vom Berge herunterkommt, mit algemeinem Applaudissement empfangen. Beim weiblichen Theil des Publikums verwischt sich dieser erste Eindruk nie; Kafka ist in ihren Augen der erste Schauspieler Teutschlands. “Heute spielt der schöne Kafka, wir müssen in die Komödie gehn,” so sagen Mütter und Töchter. Durch die Erfahrung nun überzeugt, daß seine äussere Eigenschaften hinreichen, Beifall in vollem Maasse zu erwerden, bekümmert er sich nicht, wahre Verdienste zu erlangen. [...] Seit einiger Zeit findet er Geschmak an Reisen, und da er vermutlich sehr weichherzig ist, so verschwindet er ganz unvermutet, ohne Abschied zu nemen. Binnen einem halben Jahre war er Schauspieler in Berlin, Brünn und Breslau. Durch Heraugabe einiger elenden Schauspiele hat er sich als Dichter prostituirt. [Gallerie von Teutschen Schauspielern und Schauspielerinnen (1783), 120–22)]

[translation:]

He has all the outer qualities of an actor: good looks, education, grace, but lacking soul and insight. His speech is rather incomprehensible, but only because he speaks too quickly [...] He is probably not lacking in musical knowledge, as he is himself a composer, albeit without much success. His voice, however, is rough and unpleasant, his execution unvarying; he has no dexterity, and he cannot really be considered a singer. Nevertheless, he plays all principal roles in operettas, and pleases almost everywhere. He knows the effect of his outward appearance, and always makes his debut as the Deserter in the operetta [a German version of Monsigny's Le Deserteur]. His extremely advantageous looks, put into the most flattering light by a flattering costume, work to his advantage with the entire auditorium and especially the female half, and nearly always, at his first appearance, as he descends from the mountain, he is received with general applause. With the female portion of the audience, this impression is never dimmed; Kaffka in their eyes is the leading actor in Germany. "Today the handsome Kaffka is playing, we must go to the theater," so say mothers and daughters. Convinced through experience that his outer qualities are sufficient to gain the full measure of approval, he does not bother to earn it. [...] For some time he has had the taste for travel, and as he is apparently very tender-hearted, he disappears entirely unexpectedly, without taking his leave. Within half a year he was an actor in Berlin, Brünn, and Breslau. Through the publication of several miserable plays, he has prostituted himself as a poet.

The following entry in the Gallerie gives a cutting description of Kaffka’s wife Theresia, née Rosenberger: “ [...] seit ihrem dritten Jahre beim Theater, hat aber demungeachtet nicht die mindesten Fortschritte in ihrer Kunst gethan [...]" ("[...] in the theater since the age of three, she has nevertheless made not the least progress in her art [...]"). Recke & Napiersky write that Kaffka’s wife was frivolous and unfaithful, and the couple is said to have divorced in the early 1780s.

Kaffka was in Breslau for several years in the 1780s with the Wäser company, moving in 1789 to Riga (where he was eventually to settle and die), then Dresden, Dessau, St. Petersburg, and back to Riga in 1801, where he established a lending library and continued to write and publish. Kaffka subsequently traveled to Stockholm, Copenhagen, and Graz, where he briefly directed the theater around 1813, before returning to Riga. According to Recke & Napiersky, Kaffka died suddenly in the dressing room after a performance of the pasticcio singspiel Rochus Pumpernickel, in which he played the role of Borthal, who sings the aria “Der Tod packt mich schon an” (“Death has already seized me,” sung to the melody of “Wer niemals einen Rausch hat g’habt” from Wenzel Müller’s Das Neusonntagskind).

Silhouette of Kaffka

(New York Public Library)

Kaffka’s work as a composer has been little studied. According to Gerber, he composed symphonies, masses, vespers, a Requiem, singspiels (Gerber lists thirteen), oratorios (Gerber lists two, including Der Tod Ludwig XVI), and ballets. The RISM catalog includes 21 listings under Kaffka’s name; IMSLP links to digitized images of four symphonies in full manuscript score, an engraved edition of the melodrama Rosemunde (1784), and a manuscript copy of a collection of arias and ensembles from German singspiels, published in Breslau in 1785.

As a composer, Kaffka is perhaps best known for the scathing accusation of musical plagiarism in a 1786 review in Cramer’s Magazin der Musik of the composer’s singspiel Bitte und Erhörung:

Dies Werklein ist von einer gewissen Seite ganz besonders merkwürdig. Um erst von dem kauderwelschen Sammensurium [gibbering hodgepodge] seines poetischen Inhalts einige Nachrich [sic] zu geben; so dient zu wissen, daß darinn der alte gute Orpheus sogleich auftritt, und sich an jene glücklichen Zeiten erinnert, wo er mit seinem Saitenspiel noch etwas Göttliches hervorzubringen vermochte; jetzt aber klagt, daß diese verschwunden sind, und mit ihnen die Hofnung seiner Unsterblichkeit! […]

Der musikalische Theil dieses Werks ist aber eigentlich, warum dieses Stück erst recht merkwürdig wird. In der That muß man jetzt, wie es scheint, die Composition und die Setzkunst nicht mehr für einerley halten. Man muß sich bey ersterer näher an die Etymologie des Worts anschliessen. Herr Kaffka hat dieß Werklein im eigentlichsten Verstande componirt, das heißt: die ganze Musik ist aus Nauman, Benda, Gluck, Schuster, und ausserdem aus den Werken der ganzen musikalischen Christenheit auf Erden ausgeschrieben und zusammengesetzt. Die Sache ist hier zu grob gemacht, als daß dem Räuber noch die Ausflucht einer Ausflucht einer unwilkührlichen Reminiscenz übrig bliebe, und zu strafbar, daß man dazu schweigen sollte. Gleich die erste Arie, ganz aus Hrn. Capellm. Naumanns Cora genommen! Wäre diese nun noch bloß abgeschrieben, und hätte man sie so gelassen, wie sie da steht, so würde man gleich des eigentlichen Verfassers Arbeit erkennen: aber so ist sie mit Zusätzen, Ausfüllungen, Dehnungen, Verzierungen vom Hernn Kaffka aufs scheußlichste zugleich entstellt. [...]

Die 6te und letzte Arie aus Glucks Orpheus: Che faro &c. so entstellt, daß sie kaum kennbar ist; es war aber auch wohl die Absicht. [...]

Ich fürchte, daß kein Takt bleibt, von dem dieser unverschämte Plagiarius im Ernste behaupten könnte, daß er aus seiner Erfindung entsprungen. Ich habe den Auftrag vom Hrn. Capellm. Naumann Hrn. K. wissen zu lassen, daß Ersterer über die Art, wie man seine Werke durch eine solche Ausschreibung und Zusetzung verdirbt, sehr empfindlich ist, und daß er sich diese Plagia in Zukunft verbeten haben wolle. Für neue Auflagen seiner Werke, fals [sic] sie nöthig sind, würde er schon selbst sorgen.

[Magazin der Musik, 5 Aug 1786, 872–78]

[translation:]

This little work [Werklein] is from a certain perspective entirely and especially noteworthy. First to give some account of the gibbering hodgepodge [von dem kauderwelschen Sammensurium] of its poetic content: it is helpful to know that good old Orpheus immediately appears, reminiscing about that happy time when he was able to bring forth something divine by plucking the strings; but now he complains that these times are gone, and with them his hope of immortality! . . . [The review goes on to dissect the absurd plot in some detail.]

The musical portion of this work is, actually, what makes this piece especially noteworthy. In fact, it appears that one must no longer consider “composition” and “writing music” [Setzkunst] one and the same thing. One must stick more closely to the etymology of the former. Herr Kaffka has “composed” this little work in the truest sense, namely: all of the music is copied and pieced together from Naumann, Benda, Gluck, Schuster, and from the works of all musical Christendom on earth besides. But this is too coarsely put, in that the thief would still have the excuse of unintentional reminiscence, yet is too criminal for one to remain silent. Even the first aria is taken entirely from Kapellmeister Naumann's Cora! [Johann Gottlieb Naumann's Swedish opera Cora och Alonzo] If this had been simply copied, and left as it stands, one would immediately recognize the actual author; but it is most horribly filled with additions, fillings in, extensions, and embellishments by Herr Kaffka . . . [The reviewer goes on to describe in detail more musical thefts.

The sixth and last aria, from Gluck's Orpheus, "Che faro &c.," is so disfigured that it is scarcely recognizable, which was probably the intention. . . I fear that not a bar remains that this brazen plagiarist can seriously claim to have hatched from his own invention. . . I have been commissioned by Herr Kapellmeister Naumann to let Herr Kaffka know that the former is very sensitive to the way in which his work is corrupted by this copying and supplementation, and that he forbids these plagiarisms in the future. He will himself provide for any new editions of his work, if such are necessary.

Kaffka’s writings as an author are quite extensive, although, like his music, little studied; the most thorough list of his writings is found in Gottzmann & Hörner (2007, 401–3; they list Kaffka under “Engelmann”). He tried his hand at nearly every genre of the time: his plays include comedies, tragedies, farces, and singspiels; his other writings include collections of historical and biographical tales and anecdotes, novels, histories, pamphlets, translations, and adaptations.

Surprisingly, given Kaffka’s poor reputation, his comedy Sechs Freyer und keine Braut is quite entertaining. It is the story of six suitors who vie in vain for the hand of Wilhelmine, the sixteen-year-old niece of Bering, a kindly but cantankerous middle-aged man afflicted with gout, whose tagline, repeated several times in the course of the play, is “Zehntausend Schock Teufel!” (roughly: “600,000 devils!”; a “Schock” is equal to three score). At the request of his dying brother, Bering took in Wilhelmine at the age of two, and he has always regarded his niece as compensation for the loss of his own beloved wife, who had died giving birth to their only child, who also died.

The six suitors give Kaffka the opportunity to poke fun at a variety of character types: Waldheim, an earnest, self-effacing, and impecunious young clerk; Lizentiat Horn, a two-faced schemer, who peppers his conversation with French phrases and lusts after Wilhelmine’s large dowry, which he believes will buy him a noble “von”; Hauptmann [Captain] von Riedel, an upright but stiff military man; Von Valentini, a supercilious and narcissistic heir to a fortune of a half million left him by his father Valentin (the Italianate final ‘i’ in the son’s name is another of his affectations); Bering’s old friend Kommerzienrath Arnold, a middle-aged Swede, heretofore a confirmed bachelor, who reminisces with Bering about their youthful womanizing, and is drunk throughout the second and much of the third acts; and Kleeborn, a journalist, critic, and would-be intellectual, whose nasty reviews overcompensate for his own utter lack of creative talent.

In the opening scene, a conversation between Wilhelmine and her maid, the unusually learned and Latin-quoting Lottchen, we learn that Wilhelmine harbors a deep secret that prevents her from choosing any of the six suitors. In the fourth scene of Act III, Wilhelmine finally confesses her secret to Lottchen: she cannot choose any of the suitors, “weil ich eine Mannsperson bin” (“because I am a man”)—foreshadowing Jack Lemmon’s final words to Joe E. Brown in Some Like It Hot. Kaffka concocts an implausible story to explain this fourteen-year masquerade, without, however, explaining how a two-year-old helpless orphan would initially have pulled it off.

The first four of the suitors (Waldheim, Horn, Riedel, and Arnold) are introduced one by one in Act I; Valentini and Kleeborn first appear in Act II. We make the acquaintance of Valentini in Act II, scene iv, as the company relaxes and takes coffee after dinner in Bering’s garden house. Valentini’s bombast is immediately apparent from his very first line: “Auf den Fittigen der Liebe führt Amor und Cythere den zärtlichsten Valentini zu den Füssen der Huldgöttinnen schönste” (“On wings of love, Amor and Cythere lead the most tender Valentini to the feet of the goddess most beautiful”). His speeches continue in this vein, littered with classical and literary allusion, with reference wherever possible to the wounds he suffered during his heroic exploits in the “American” war. Twice during the course of the play he improvises poems (not very good ones). During his first scene, Valentini asks Wilhelmine for permission to paint her. When his multiple talents are remarked upon, he says: “Ohne Ruhm zu melden: ich bin Dichter, Maler, Musikus, und allen dreien gleich stark und unnachahmlich. Und im Tanzen, meiner Lieblingsleidenschaft, da such ich meines Gleichen” (“Not to boast, but: I am a poet, painter, musician, and equally strong and inimitable in all three. And in dancing, my favorite passion, I have yet to find my equal”). He later claims to have studied music composition in Venice, painting and poetry in Rome, and dancing with Noverre (II:x).

Valentini’s speech mentioning Mozart is delivered in Act II, scene x, after Riedel interrupts an ongoing conversation (which the audience has not been party to) between Wilhelmine and Valentini. Riedel asks what they have been talking about; Wilhelmine answers that they are having a friendly dispute over “our composers” (meaning German ones). Valentini opines that Italy is “inundated” (“überschwemmet”) with composers, but the number of those who earn the title “artist” is small. The worthy Italians he names are: Niccolò Piccinni (1723–1800), Pasquale Anfossi (1727–?1797), Antonio Sacchini (1730–1786), Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi (1728–1804), Giovanni Paisiello (1740–1816), Antonio Salieri (1750–1825), Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801), and Giuseppe Sarti (1729–1802), all leading Italian opera composers of the period. He then lists German composers who can be ranked with these Italians; in addition to “Mozard,” he names Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–1787), Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741–1801), Georg Benda (1722–1795), Anton Schweitzer (1735–1787), Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804), “Bach” (very likely Carl Philipp Emanuel, 1714–1788), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814), and Christian Gottlob Neefe (1748–1798). Ironically, and perhaps intentionally, three of the composers Kaffka names (Naumann, Benda, and Gluck) are ones from whom he himself had been accused of stealing.

In fact, Kaffka seems to draw on his own life for comic material elsewhere in the play. In Act II, scene viii, Kleeborn and Horn discuss material that is to appear in the next issue of Kleeborn’s literary magazine. Kleeborn first gives the (intentionally parodistic) titles of two articles slated to appear in the issue: “Gründliche Beschreibung, wie man spanische Wolle hier im Lande gewinnen kann, ohne spanisches Klima zu haben” (“An In-depth Description of How Spanish Wool Can Be Obtained in These Parts without Having a Spanish Climate”), and “Entlarvtes System des sämtlichen Freymäurerordens, von einen Ungeweihten der Welt unparteyisch vorgelegt und enträthselt” (“The System of the Entire Order of Freemasons Revealed, by a Non-Initiate, Impartially Presented and Explained”). He then asks Horn to peruse a draft of his review of an actor. Horn reads aloud from Kleeborn’s draft: “Herr Schnips wäre zum Schauspieler ganz gut gemodelt, aber sein Kopf wahrhaftig nicht. Er gehört unter die Pfuscher, weil er glaubt, daß er schon ein gemachter Mann sey. Sudler, wahrhaftig nichts mehr als Sudler ist er” (“Herr Schnips would be quite well formed to be an actor, only his head truly is not. He belongs among the bunglers, because he believes that he is a successful man. A hack, he’s truly nothing more than a hack”). This seems likely to be a parody of the unflattering description of Kaffka’s acting abilities in the Gallerie von Teutschen Schauspielern.

Later in the scene in which Valentini lists worthy Italian and German composers, he performs his own cantata, on the story of Procris and Cephalus, “die ich vor zwei Jahren in Wien komponirt und mit dem einstimmigsten Beifall aufgeführt habe” (“which I composed two years ago in Vienna and performed with the most unanimous approval”; that Valentini says “most unanimous” is one of the subtle linguistic touches that suggest Kaffka may be better than his reputation). Valentini accompanies himself on the keyboard as he sings, with Riedler on the violin, which Valentini has asked him to play “as softly as possible” (Riedler uses a mute). After Valentini concludes, Waldheim notes that he recognizes the text as by Germany’s “Virgil” Karl Wilhelm Ramler, something Valentini had, perhaps intentionally, neglected to mention. (The cantata text, which is included in full in Kaffka’s play, does in fact come from scene 5 of Ramler’s one-act “singspiel” text, Cephalus und Prokris.) Kleeborn characteristically says: “Das Gedicht scheint mir etwas zu lange” (“The poem seems to me somewhat too long”); but Kaffka has, in fact, cut the passage slightly, and it represents only a portion of one scene of Ramler’s longer work; thus Kleeborn has unwittingly demonstrated once again his own ignorance and philistinism. Kleeborn then asks whether Valentini composed the music himself; Valentini answers that he has. Kleeborn responds: “Ih nun—ich meyne nur—daß—Ideen von andern Komponisten entlehnen und sie in dem Geist seines Textes zusammensetzen, ein sehr grosses und glückliches Verdienst sey” (“Eh well—I mean just—that—to borrow ideas from other composers and to piece them together in the spirit of his text, is a very great and fitting service”). This is surely an ironic reference to the scathing review of Kaffka’s musical plagiarism.

With self-promotional chutzpah, Kaffka includes a footnote to the cantata text: “Die Musik zu dieser Cantata, die sehr leicht und gefällig zum singen eingerichtet ist, kann man in Partitur oder in Stimmen sauber und korrekt geschrieben bei mir oder dem Verleger, Herrn Heffenland, um einen sehr billigen Preiß bekommen” (“The music to this cantata, which is designed to be easy and pleasurable to sing, can be had in score or in parts, cleanly and correctly written, from me or from the publisher Herr Heffenland, at a very cheap price”).

Johann Friedrich Reichardt, one of Valentini's worthy German composers, set Ramler's text as a melodrama that was performed in Hamburg in 1777.