Commentary

(pdf)On 23 Sep 1790, Mozart left Vienna for Frankfurt with the violinist Franz de Paula Hofer, to attend the festivities surrounding the election and coronation of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor. The pair arrived in Frankfurt on 28 Sep. On Fri, 15 Oct, several days after the coronation, Mozart gave a concert at 11 in the morning in the city’s theater, the Komödienhaus, which had been completed in 1782 (see our entry for 2 Aug 1783). Participating in the concert with Mozart were soprano Margarethe Luisa Schick (see our entry for 1 May 1791) and castrato Francesco Ceccarelli, both at that time members of the court music establishment in Mainz. The concert seems to have been something of a disappointment, with poor turnout and meager proceeds (on Mozart’s Frankfurt concert, see Glatthorn 2017, here esp. 105–10). Mozart departed Frankfurt soon after, arriving in Mainz by 17 Oct. On Wed, 20 Oct, Mozart performed in a concert in the Akademiesaal at the Electoral Palace in Mainz, again with Ceccarelli, and now with the soprano Franziska Josepha Hellmuth, who was a member of both the Mainz Hofkapelle and of the city’s Nationaltheater.

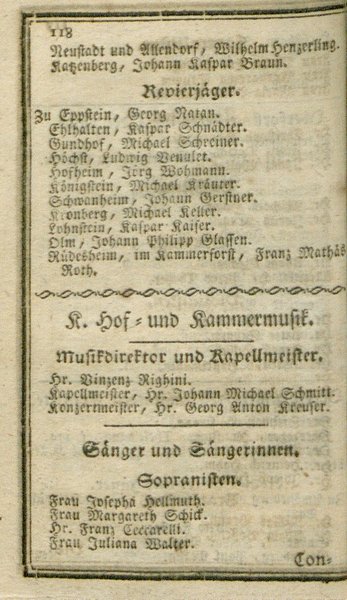

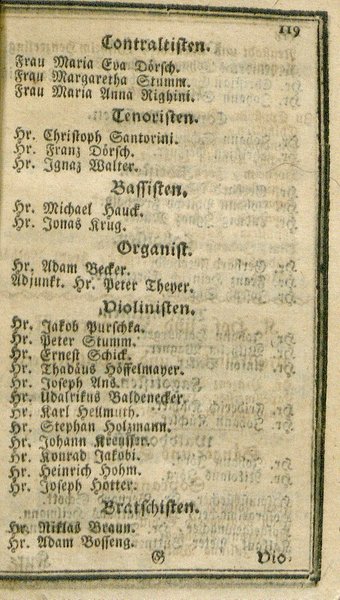

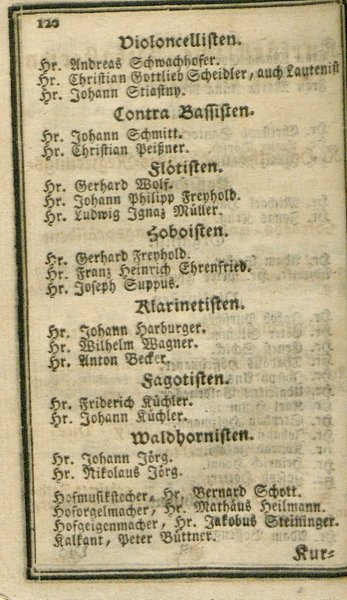

Hof- und Kammermusik,

Kurmainzischer Hof- und Stats-Kalender, 1790, 118–20

This list shows Vincenzo Righini as court music director, and Franziska Josepha Hellmuth, Margarethe Luisa Schick, and Francesco Ceccarelli as sopranos. The orchestra at Mozart’s performance on 20 Oct 1790 would have been drawn from the list of instrumentalists shown here.

Mozart mentions the Mainz concert in a letter to his wife sent from Mannheim on 23 Oct 1790:

— ich habe den Tag vor meiner Abreise beym Churfürsten gespielt, aber magere 15 Carolin erhalten — [Briefe, iv:119]

— On the day before my departure [from Mainz] I played at the Elector’s, but received a meagre 15 Carolin —

The concert in Mainz was also reported on 21 Oct 1790 in the Privilegierte Mainzer Zeitung (Dokumente, 331). The previously unknown participation of Ceccarelli and Hellmuth is documented in the recently discovered travel diary of Count Franz Joseph von Zierotin (1772–1845), who had attended the Frankfurt coronation as a page-boy for the Bohemian delegation, and was in Mainz on the day of Mozart’s performance (on Zierotin, see our entries for 20 Oct and 22 Oct 1790).

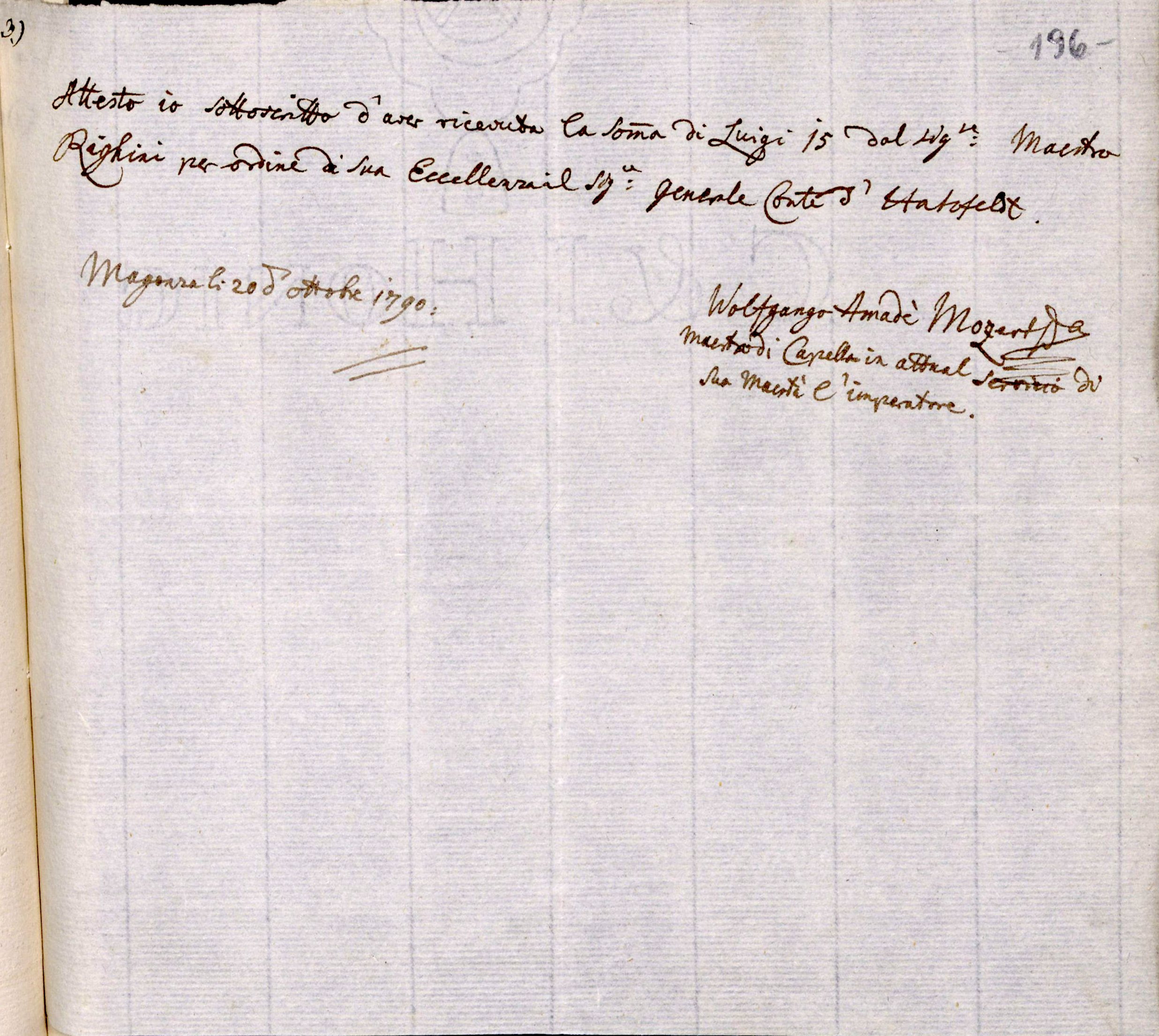

Mozart’s autograph receipt for his honorarium in Mainz was discovered in 2012 by Franz Stephan Pelgen in files of the Mainz court music administration that are now preserved in the Hatzfeld family archives in Wrocław (Breslau; on these documents and Mozart’s receipt, see Pelgen 2021). At the time of Mozart’s performance, the de facto intendant of court music in Mainz was Count Franz Ludwig von Hatzfeld (also Hatzfeldt, 1756–1827), who was never officially appointed to the position. Franz Ludwig was a younger brother of Count August Clemens von Hatzfeld (1754–1787), Mozart’s friend and a brilliant amateur violinist for whom Mozart composed the solo violin part in the scena con rondò “Non temer, amato bene,” K. 490, written for the production of Mozart’s Idomeneo at the theater of Prince Auersperg in Vienna in 1786 (on August Clemens, see our entry on that production). The next older brother of Franz Ludwig was Count Hugo Franz von Hatzfeld (1755–1830), whose letter to Gustav Friedrich Wilhelm Großmann regarding Idomeneo is the topic of our entry for 23 Mar 1786. The older half-brother of these three was Count Clemens August Johann Nepomuk von Hatzfeld, husband of Countess Maria Anna Hortensia von Hatzfeld (née Zierotin), an extraordinary amateur soprano, who sang the role of Elettra in the 1786 production of Idomeneo in Vienna. (On Countess Hatzfeld, see our entry on her performance of “Tutte nel cor vi sento” in Bonn.) Countess Hatzfeld helped organize Mozart’s concert in Frankfurt in 1790 (see Glatthorn 2017, 105ff), and she may also have helped arrange for Mozart’s performance in Mainz through her close family ties in that city.

According to Mozart’s receipt, he received his honorarium from Mainz music director Vincenzo Righini (1756–1812). Righini worked in Vienna from at least 1777 until 1787, before taking up the position in Mainz. As Pelgen explains (2021, 56–57), Righini served as deputy for Count Franz Ludwig when the latter was out of town, Although Franz Ludwig was generally quite hands-on in his management of court music in Mainz, he was also a Major General in the electoral army, leading a regiment bearing his family name: hence the reference to him in the receipt as “Sig:re Generale Conte d’Hatzfeldt.” Franz Ludwig was away from Mainz for around a year beginning in May 1790, leading his regiment (apparently rather ineffectually) in attempts to retake Liège during the Liège Revolution. Thus he almost certainly was not in Mainz during Mozart’s visit, and Righini was acting in the count’s stead.

Mozart writes in his letter of 23 Oct 1790 that he was paid “15 Carolin.” A Carolin (Karolin) was a gold coin worth 11 gulden (fl), so Mozart’s payment for the performance was 165 fl; this is the amount recorded in the accounts of the court musical establishment in Mainz (Dokumente, 331). Mozart’s autograph receipt refers to 15 “Luigi,” an Italian translation of “Louis,” referring to the French gold coin, the “Louis d’or,” which had been the inspiration for the creation of the Carolin.

Mozart refers to his honorarium in Mainz as “mager” (“meager”). But 165 fl was well over one-third of the 450 fl that Mozart had received at the beginning of 1790 for composing Così fan tutte (Edge 1991). From that perspective, 165 fl for one evening’s work at a court concert for which he had no expenses seems not unreasonable. As Pelgen has shown (2021, 59), the court music establishment at that time had an annual cap of 1000 fl on payments to visiting musicians, and Mozart’s honorarium thus amounted to one-sixth of the annual budget. In evaluating Mozart’s reaction, we need to remember that he was already in serious financial distress in Vienna before leaving for the coronation in Frankfurt, an expensive trip that he apparently paid for out of his own pocket. Although we do not know how much Mozart netted from his concert in Frankfurt, the amount was apparently disappointing, and so far as we know, he did not make any other money while in Frankfurt. He may, then, have been hoping against hope that performing in Mainz might save him from returning to Vienna even further under water financially than when he left. From that point of view, his honorarium of 165 fl in Mainz may indeed have seemed “meager.”