Commentary

(pdf)One of the most famous of all images of Mozart is a watercolor portrait by Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle, painted at some point during the Mozart family’s stay in Paris from 18 Nov 1763 to 10 Apr 1764. The portrait depicts a young (and still quite tiny) Wolfgang playing a harpsichord, with Nannerl standing to his left, posed as if she were singing, and Leopold standing behind him playing the violin. All three are shown in profile, as was Carmontelle’s usual practice.

Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle, watercolor portrait of the Mozarts (1764), Musée Condé

(Wikimedia Commons)

At least two versions of this watercolor are known to survive, both assumed to have been painted by Carmontelle: one in the Musée Condé and one in The British Museum. The two versions of the watercolor are very similar, but can be readily distinguished by comparing details, such as the foliage of the trees or the shading lines.

At some point within approximately the first year after the portrait was painted, a beautiful single-color engraving was based on it. The plate is signed by Jean-Baptiste Delafosse, who almost certainly engraved it himself.

Jean-Baptiste Delafosse, single-color engraving based on Carmontelle’s

watercolor portrait of the Mozarts (1764)

(The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

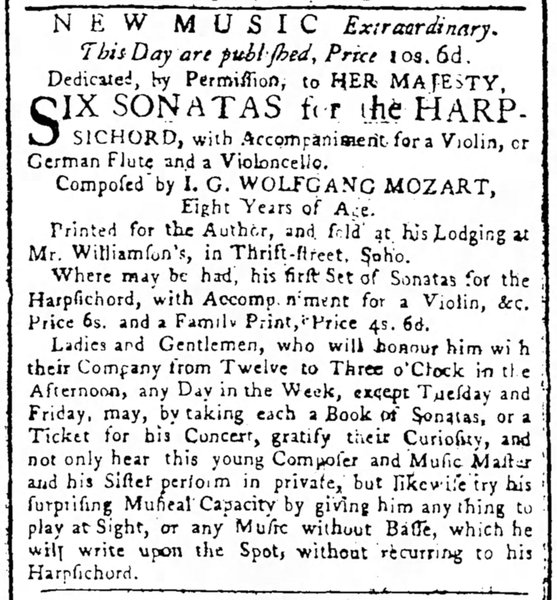

The inscriptions read:

L. C. De Carmontelle del. Delafosse Sculp. 1764.

LEOPOLD MOZART, Pere de MARIANNE MOZART, Virtuose âgée de onze ans

et de J. G. WOLFGANG MOZART, Compositeur et Maitre de Musique

âgé de sept ans.

What is now the earliest known advertisement of this engraving was published in L’Avantcoureur on 21 Jan 1765. The advertisement is (apart from inconsequential editorial differences) identical to one published slightly later, in the Feb 1765 issue of the Mercure de France; this version is already well known and is included in Dokumente (42). The exact date of publication of the Feb issue of the Mercure de France remains unknown, but this issue of L’Avantcoureur would have appeared at least 11 days earlier. Although the difference in dates is small, the chronology of Carmontelle’s portrait and the prints based on it remains poorly understood, so any bit of new evidence may potentially contribute to our understanding of the portrait’s history. (On a separate hand-colored print based on the portrait, see Salmon, forthcoming.)

The earliest known reference to the portrait and a print based on it is found in Leopold Mozart’s letter of 1 Apr 1764 to Lorenz Hagenauer in Salzburg, just nine days before the Mozarts left Paris. Leopold writes:

M. de Mechel ein Kupferstecher arbeitet über Hals und Kopf unsere Portraits die H: v Carmontel |: ein Liebhaber |: sehr gut gemahlt hat, zu stechen. der Wolfg: spiehlt Clavier, ich stehe hinter seinem Sesel und spiele Violin, und die Nannerl lehnt sich auf das Clavecin mit einem Arm. mit der anderen hand hält sie musicalien, als säng sie. [Briefe, i:142]

Monsieur de Mechel, a copper engraver, is working in a mad rush to engrave our portrait, which Herr von Carmontelle (an amateur) has painted very well. Wolfgang plays the keyboard, I stand behind his chair and play the violin, and Nannerl leans on the harpsichord with one arm. With the other hand she holds music, as if she were singing.

This letter provides a terminus ante quem for at least one version of Carmontelle’s painting, and it shows that already by early Apr 1764 there was a plan in progress to base an engraving on it. Leopold is referring to the Swiss engraver Christian von Mechel (1737–1817), who would presumably have been working “über Hals und Kopf” because the Mozarts were about to leave Paris for London, and Leopold probably hoped to take a stock of the finished print with him to London to sell or to give to potential patrons. In the event, however, the Mozarts left Paris on 10 Apr 1764, almost certainly without any finished prints in hand. The first evidence that a finished print based on Carmontelle’s portrait was available in England is an advertisement in The Public Advertiser on 20 Mar 1765, eleven months after the Mozarts had arrived in London (the advertisement is transcribed in Dokumente, 43).

The first English advertisement of the engraving based on Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait.

The Public Advertiser, 20 Mar 1765

(newspapers.com)

Because of Leopold’s reference to Mechel, it has sometimes been suggested in the Mozart literature that Mechel must have been the engraver of the single-color print, which Delafosse then signed “in the plate” (see, for example, King 1984, 170n23). But there is no evidence to support this notion, and considerable contextual evidence against it. Mechel is not known ever to have worked for or with Delafosse; and by 1764, Mechel was already well established in Paris as an independent engraver in his own right, so he is unlikely to have allowed someone else to take credit for his work. In any case, the single-color engraving of Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait is not a good match for Mechel’s style.

Christian von Mechel, engraving (1762) based on Gabriël Metsu’s painting of Nostradamus

(Library of the University of Tartu)

Delafosse, on the other hand, engraved many of Carmontelle’s paintings around this time, and the engraving style of the Mozart portrait is consistent with other engravings signed by Delafosse and based on Carmontelle’s paintings.

Jean-Baptiste Delafosse, engraving (1765) based on Carmontelle’s watercolor portrait of

Gaspar-François de Fontenay

(Wikimedia Commons)

What is usually taken to be the earliest reference to a finished version of a print based on Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait is found in a private letter dated 13 Dec 1764 from Baron Grimm in Paris to the young prince (later duke) Ernst Ludwig von Sachsen-Gotha (1745–1804). Grimm writes:

Votre Altesse a peut-être entendu parler de petits enfants que leurs talents pour la musique, et particulièrement pour le clavecin, ont fait admirer de tout Paris l’hiver dernier; leur portrait sera joint au premier paquet. [...] [Tourneux 1882, 38]

Your Highness has perhaps heard talk of the young children whose musical talents, especially on the harpsichord, aroused the admiration of all Paris last winter; their portrait is included in the first packet. [...]

It is generally assumed that Grimm is referring to a print, not to one of Carmontelle’s actual watercolors, although he does not explicitly say so. But it seems fairly safe to assume that Grimm sent Ernst Ludwig a print based on Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait. The earliest known public reference to such a print is now the advertisement in L’Avantcoureur on 21 Jan 1765. That advertisement almost certainly refers to the single-color engraving by Delafosse; any hand-colored prints, if they existed by this time, would have taken much more labor to produce, and would presumably have been considerably more expensive. The first London advertisement of the single-color engraving appeared just two months later, on 20 Mar 1765.

Grimm’s letter and the two advertisements suggest that the single-color engraving was finished and initially printed no later than mid Dec 1764; that it began to be offered for sale to the public the following month; and that a stock of these prints was sent to London around that same time. There is no evidence that the single-color engraving was finished or available before Dec 1764. Mechel’s role, if any, in the production of the single-color engraving remains unknown. It is unlikely, in any case, that he had anything to do with the prints produced from the plate signed by (and almost certainly engraved by) Delafosse. It has sometimes been suggested that Mechel completed an engraving around the time of the Mozarts’ departure from Paris, but that his version was rejected for some reason, and Delafosse was brought in to create a new one. While possible, this is speculative, and no known direct evidence supports it. Given that Delafosse seems to have been Carmontelle’s principal engraver at that time, it is unlikely that Carmontelle himself would have picked Mechel over Delafosse to produce a plate for a single-color engraving of Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait. Whatever the case may be, Mechel left Paris to return to his native Basel in Oct 1764, where he opened an art dealership and engraving shop (Portalis & Béraldi 1882, 72).

It is uncertain which of the Carmontelle watercolors of the Mozarts served as the basis for the single-color engraving by Delafosse. Because of the nature of the medium, the level and precision of linear detail in the engraving is much higher than in the watercolor. The engraver has, in effect, produced an engraved “translation” of one of Carmontelle’s watercolors, not an exact rendering.

Detail comparison of the Condé version of Carmontelle’s watercolor with Delafosse’s engraving

The single-color engraving of Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait is also relevant to the question of the claimed ages of the Mozart children, particularly Wolfgang, whose true age appears to have come into question when they were in London (see our entry for 10 May 1765). The inscription on the Delafosse engraving gives Wolfgang’s age as 7 and Nannerl’s as 11; this is presumably meant to indicate their ages at the time Carmontelle painted them, not necessarily at the time the engraving was finished. But we do not know precisely when the portrait was painted. The Mozarts arrived in Paris on 18 Nov 1763 and departed on 10 Apr 1764. From 24 Dec 1763 to 8 Jan 1764 they were in Versailles, and (given that the portrait shows them in Carmontelle’s Paris studio) they cannot have posed for the portrait during that interval. In any case, the position of Carmontelle’s name in Leopold’s travel notes suggests that the Mozarts met him after their return from Versailles (Briefe, i:144). If that is correct, then the portrait must have been painted at some point between 9 Jan and 1 Apr 1764, the date of Leopold’s letter to Hagenauer. Wolfgang turned 8 on 27 Jan 1764. So it is just (barely) possible that the age given for Wolfgang on the engraving was literally correct, provided that Carmontelle finished the painting before Wolfgang’s birthday.

But all evidence suggests that Wolfgang was generally believed in Paris to have turned 7 (not 8) on his birthday in 1764. Grimm’s article on the Mozarts in the Correspondance littéraire dated 1 Dec 1763, just a few weeks before Wolfgang’s birthday, states that he “aura sept ans au mois de février prochain” (will be seven this coming February [sic]; see Tourneux 1878, 410–12, transcribed in Dokumente, 27–28). Wolfgang’s actual age at the time of Grimm’s article was around 7 years and 10 months. Similarly, Grimm gives Nannerl’s age as “onze” (eleven), although she had already turned 12 on 30 Jul 1763, nearly four months before the family arrived in Paris. An article closely based on the one in Correspondance littéraire was published in L’Avantcoureur on 5 Mar 1764; it gives the Nannerl’s age as 11 and states somewhat ambiguously that Wolfgang has just “completed his seventh year” (“a eu … sept ans accomplis”; see our entry for that date). By this time, Wolfgang was in fact 8. Wolfgang and Nannerl are subsequently referred to as being, respectively, 7 and 11 years old in every other known publication from their time in Paris, when they were actually 8 and 12. The article in L’Avantcoureur began to appear in translation in German newspapers just shortly after its publication in France, also with the incorrect ages (see our entry for 5 Mar 1764). This fiction, that the children were both one year younger than their true ages, was then maintained in all publications referring to them throughout the family’s subsequent stay in England and beyond (see our entry for 10 May 1765).

It is often assumed that the misrepresentation of the children’s ages stemmed from Leopold. While this possibility cannot be ruled out, it should be noted that the references to the children in the Frankfurter Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten on 16 and 30 Aug 1763 give their ages correctly as (at that time) 7 and 12. The notice on 16 Aug was surely placed by Leopold himself, so he was evidently not attempting to misrepresent their ages when they were in Frankfurt. In fact, Grimm’s article in Correspondance littéraire is the first source to shave a year off the ages of both children. So one wonders whether Grimm, rather than Leopold, might have been the initial source of this misrepresentation—one that Leopold might then to have felt obliged to maintain, perhaps unwillingly, after they left Paris, because the false ages had already appeared so often in print. (Wolfgang’s age was also given as 7 on the title pages of his op. 1 and 2, first published in Paris in the spring of 1764 after he had turned 8; these sonatas were then also reprinted and sold in London; see our entries for 5 Mar 1764 and 9 Apr 1764.)

If we assume that the Parisian public generally believed Wolfgang to have turned 7 on 27 Jan 1764, this in turn would imply that Carmontelle (who would likely have believed it as well) painted the portrait after Wolfgang’s birthday, not before. If that is correct, then the date of the portrait (at least in its initial version) can be further narrowed down to the period between 27 Jan and 1 Apr 1764.

The engraving of Carmontelle’s portrait was advertised at a price of 24 sols. There were 20 sols to a French livre, so the price was equivalent to 1 livre 4 sols (there was, however, no livre coin in circulation at that time). In a letter to Hagenauer from London on 9 Jul 1765, Leopold writes:

Diese Kupfer sind gemahlt worden, da der Bub 7. Jahr und das Mädl 11. Jahr alt ware, gleich bey unserer Ankunft in Paris. Mr: Grimm ist der Anstifter davon, und in Paris wird das Stück für 24.Sols, so mehr dann 30. Xr: beträgt, bezahlt. [Briefe, i:191]

This engraving was made when the boy was 7 years old and the girl 11, right after our arrival in Paris. Monsieur Grimm was the instigator of this, and in Paris the price was 24 sols each, thus more than 30 kreuzer.

(Leopold seems to have forgotten that Hagenauer would probably have remembered that Nannerl had turned 12 well before they reached Paris.) Leopold’s “more than 30 kreuzer” does not follow his own rules of thumb on French currency, as explained in his letter to Hagenauer of 8 Dec 1763 (Briefe, i:115). There he writes that for simplicity in his own mental reckoning, he thinks of one French sol as equivalent to one kreuzer. By this rule, one would have said that the price of the engraving was about 24 kr. In fact, according to the rates in force in the Habsburg lands at that time, which set the value of the French louis d’or to 8 fl 37 kr, 24 sols would have been equivalent to a bit less than 26 kr, quite close to Leopold’s rule of thumb. (In France, one louis d’or was equivalent to 24 livres, or 480 sols.) But Leopold’s “more than 30 kreuzer” implies that he may have been reckoning here according to some other system. One possibility is the accounting used in Bavaria at that time, under which a gulden was taken to consist of 72 kr, rather than 60 kr, as in the Habsburg lands. Using the Bavarian system, 24 sols would have been equivalent to 31 kr, consistent with what Leopold writes. Wolfgang’s op. 1 and 2 were each advertised at a price of 4 livres 4 sols (84 sols), nearly four times the price of the engraved portrait.

The advertisement in L’Avantcoureur also offers Wolfgang’s op. 1 and op. 2 (K. 6–9), both of which had been published the previous year (see our entry for 9 Apr 1764). The plates were “no longer in France” because Leopold had taken them to England, where he used them to reprint the edition, before passing the plates on to the music publisher Bremner. The advertisement ends with a reference to “une grande symphonie de Chambray, avec flutes [sic] ou hautbois & cors ad libitum” (a grand symphony by Chambray, with flutes or oboes, and horns ad libitum). The reference is to the aristocratic amateur composer Louis-François, marquis de Chambray (1737–1807).

The Delafosse engraving of the Mozarts became widely known during the composer’s lifetime. Daines Barrington evidently acquired a copy of it, probably directly from the Mozarts, perhaps when he visited them in June 1765 and tested Wolfgang’s skills. Barrington’s report on this visit, published in 1771 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, includes a description of the engraving (see Barrington 1771, 56; for more on Barrington, see our entry on his anecdote about Samuel Wesley and Mozart). Leopold evidently had received a stock of the engravings in London no later than March 1765, and he continued to distribute them during the remainder of the family’s European tour. In our entry for 9–10 Aug 1765, we describe a surviving exemplar apparently acquired by someone in Dunkirk when the Mozarts passed through that town; the dates of their visit are written on the back of the exemplar in iron-gall ink by a contemporaneous hand: “ils Etoient a Dunkerque les 9 & 10 aout 1765” (they were in Dunkirk on 9 and 10 August 1765).

In his letter to Hagenauer of 9 Jul 1765, Leopold writes that he has asked Grimm to send Hagenauer a packet of the prints; the packet would have contained at least 60 copies (and probably more), because Leopold instructs Hagenauer to send 30 each to the dealers Lotter in Augsburg and Haffner in Nuremberg (Briefe, i:191). Advertisements of the print sometimes appear in newspapers along the Mozarts’ homeward journey from their tour, for example, an advertisement in the Donnstags-Nachrichten of Zürich on 9 Oct 1766 (Dokumente, Nachtrag, 520):

Advertisement for Delafosse’s engraving of Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait

Donnstags=Nachrichten (Zürich), no. 41, 9 Oct 1766 [4]

(e-rara.ch)

The Delafosse engraving is described in Forkel’s (quite inaccurate) entry on Wolfgang in his Musikalischer Almanach for 1784 (Musikalischer Almanach für Deutschland auf das Jahr 1784, 104; Dokumente, 195–96), and again in the article on Leopold Mozart in Gerber’s Lexikon, published in 1790 (Historisch=Biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler, vol. 1, col. 977; Dokumente, 337). Delafosse’s engraving of Carmontelle’s Mozart portrait was then, without question, the most famous and widely distributed image of Wolfgang during the composer’s lifetime.