Commentary

(pdf)In Nov 1766 the Mozart family was in the final stages of its homeward journey from a long tour of Europe that had begun in 1763. The Mozarts spent two days (often said to be 4 and 5 Nov) in the Swabian town of Dillingen an der Donau on their way toward Augsburg, Leopold Mozart’s hometown. At some point after leaving Dillingen and before reaching Augsburg, where they stayed just one day (probably 7 Nov), the 10-year-old Mozart is said to have engaged in a contest on the organ with the 12-year-old prodigy Joseph Sigmund Eugen Bachmann (later Sixtus Bachmann, 1754–1825).

This story has long been a staple of the Mozart literature, but it rests on a single source: a short biography of Bachmann published 24 years after the fact by Johann Friedrich Christmann (1752–1817) in Bossler’s Musikalische Korrespondenz on 24 Nov 1790. (The event is not mentioned in Leopold Mozart’s surviving letters.) The relevant portions read:

[col. 163]

Brief von Hrn. Pf. Christmann, der einige kurze

Nachrichten von den Lebensumständen

des Hrn. P. Bachmanns enthält

[...]

Herr P. Sixt Bachmann im Kloster March=

thal an der Donau ist gebohren zu Kettershau=

in der Gräfl. Babenhausischen Herrschaft den

18 Julius 1754.

[...]

Ein glüklicher Umstand für den ju=

gendlichen Virtuosen war die Liebhaberei zur

[col. 164]

Musik des Herrn Grafen: er ließ den jungen

Bachmann nicht nur öfters zu sich kommen und

vor ihm spielen; sondern suchte auch durch seinen

lauten Beifall und durch Belohnungen seinen

Eifer noch mehr anzufrischen und seinen Ehrgeiz

zu immer größerer Vervollkommnung in dieser

Kunst immer reger zu machen. Hiezu benuzte

der Herr Graf insonderheit jenen Zeitpunkt, da

Herr Kapellmeister Mozart als junger Virtuose

mit seinem Vater reißte und auch auf dem gräf=

lichen Schloße die Beweise seiner Geschiklichkeit

in der Musik ablegte. Der junge Bachmann

wurde aufgemuntert, sich mit Mozart in einen

Wettstreit auf der Orgel einzulassen. Jeder

that sein äusserstes, um dem andern den Vorzug

streitig zu machen, und für beede fiel der ange=

stellte Wettstreit sehr rühmlich aus. [...]

[col. 165]

[...]

Hr. Bachmann fieng nun an, seine

erlangte Kenntnisse zum Vergnugen und Nuzen

des Publikums anzuwenden, komponirte Gleim

sanakreontische Lieder [...]

[Musikalische Korrespondenz der teutschen Filarmonischen

Gesellschaft für das Jahr 1790, no. 21, Wed, 24 Nov 1790, cols. 163–64;

Dokumente, 333]

[translation:]

Letter from Herr Pastor Christmann, containing some

brief news on the personal circumstances of

Herr Father Bachmann.

[...]

Herr Father Sixtus Bachmann, in the monastery at

Marchtal an der Donau, was born in Kettershausen

in the domain of Count Babenhausen on 18 July 1754.

[...]

A fortunate circumstance for the youthful

virtuoso was the Count’s love of music: not only did he

often have young Bachmann come play for him,

but he also strove, through open praise and rewards,

to inspire him to redouble his efforts and to animate

his desire toward ever greater perfection in this art.

To this end the Count especially made use of the

time when Herr Kapellmeister Mozart, as a young

virtuoso, was traveling with his father and was likewise

giving proofs of his skill in music at the Count’s palace.

Young Bachmann was encouraged to engage in

a contest on the organ with Mozart. Each did his utmost

to best the other, and the outcome of the contest was

very favorable to both. [...]

[col. 165]

Herr Bachmann is now beginning to turn

the fruits of his knowledge to the pleasure and use

of the public, and composed Gleim’s anacreontic songs [...]

Kettershausen, Bachmann’s birthplace, was in the domain Count Anselm Joseph Viktorian Fugger-Babenhausen (1729–1793), head of one of several aristocratic lines stemming from the famous Fugger merchant family of Augsburg. (The Babenhausen line survives; its current head is Prince Hubertus Fugger-Babenhausen.) Count Anselm Joseph Viktorian had presided over the domains of the Babenhausen line since the death of his father in 1759. Schloss Babenhausen still exists in the Swabian town of that name.

Schloss Babenhausen, aerial view

(www.fugger.de)

Christmann seems to imply, although he does not quite explicitly state, that this castle was the location of the contest between Bachmann and Mozart. But this is highly improbable, given the Mozarts’ route between Dillingen and Augsburg.

Map showing the relative locations of Dillingen, Biberbach (green), Augsburg,

Babenhausen, and Biberach an der Riss

(Google Maps)

Dillingen is about 38 kilometers northwest of Augsburg as the crow flies and 50 kilometers by road, whereas Babenhausen is around 55 kilometers southwest of Augsburg, and around 65 kilometers by road. More crucially, Babenhausen is over 50 kilometers south-southwest of Dillingen, and over 60 kilometers by road. Thus for the Mozarts to have traveled from Dillingen to Augsburg via Babenhausen would have required them to travel around 125 kilometers in the space of no more than two days—not impossible, but certainly very far out of their way from Dillingen to Augsburg.

In his Mozart biography, Nissen places the organ contest in “Biberach” (without the second ‘b’), which was taken by some to imply Biberach an der Riss, home of writer Christoph Martin Wieland:

Von dieser grossen Reise weiss man noch, dass der Knabe [Mozart] auf dem gräflichen Schlosse Babenhausen die Beweise seiner Geschicklichkeit ablegte, und dass er im Markte Biberach [sic] einen musikalischen Wettstreit auf der Orgel mit dem nachherigen Pater Sixtus Bachmann (geb. 1754, zuletzt im Kloster Marchthal an der Donau) hatte, in welchem Jeder sein Aeusserstes that, um dem Andern den Vorzug streitig zu machen. Der Ausgang war für Beyde sehr rühmlich.

[Nissen 1828, 120]

Of this great journey we also know that the boy [Mozart] had given proofs of his skill at the palace of Count Babenhausen, and that he had a musical contest on the organ in Markt Biberach [sic] with the future Father Sixtus Bachmann (born 1754, most recently in the abbey at Marchthal an der Donau), in which each did his utmost to best the other. The outcome of the contest was very favorable to both.

Except for the reference to “Markt Biberach”, this is essentially a plagiarism of Christmann’s account in 1790, which Nissen does not cite. But Biberach an der Riss is an even less plausible location for the contest: it is over 160 kilometers west southwest of Augsburg as the crow flies, and because of the intervening terrain, considerably further by road. The only point at which the Mozarts plausibly could have stopped in Biberach an der Riss was on their journey between Meßkirch and Ulm a few days before reaching Dillingen.

The implausibility of either Babenhausen or Biberach an der Riss as the location for Wolfgang’s contest with Bachmann was recognized by Ernst Fritz Schmid (1948, here esp. 156ff), who argued that the meeting can only have taken place in Markt Biberbach, just 20 kilometers north-northwest of Augsburg, and directly on the road from Dillingen to Augsburg.

19th-century map showing Biberbach and the road from Dillingen

Schmid also showed that Bachmann’s maternal grandfather Franz Joseph Schmöger was organist and regens chori of the pilgrimage church in Biberbach (St. Jakobus, St. Laurentius und Hl. Kreuz), thus establishing a link between Bachmann and the town.

Interior of St. Jakobus, St. Laurentius und Hl. Kreuz, Biberbach

(Wikimedia Commons)

The goal of pilgrims was a depiction of Christ on the cross, the so-called Herrgöttle von Biberbach, said to be the source of many miracles.

The Herrgöttle von Biberbach

(Wikimedia Commons)

Schmid notes that one of the miracles attributed to the Herrgöttle was the cure of the gravely ill Maria Anna Mozart, wife of Leopold’s brother Joseph Ignaz (Schmid 1948, 154). The story of Maria Anna’s miraculous cure is told in the third and last edition of Johann Joachim Keller’s Das spöttlich verschmähte, aber widerum glorreich erhöhte Creutz Das ist: Ausführlich- und wahrhaffte Beschreibung von der Herkunfft, Anfang, Wachsthum und Fortpfla[n]tzung der weitberühmten Wallfahrt Des Heil. Creutzes zu Marckt Biberbach in Schwaben (1762). Schmid transcribes in full Keller’s description of Maria Anna’s cure. Because this description is little known—Schmid’s book is rare, and the 1762 edition of Keller seems not yet to be available online—and because it is at least peripherally a Mozart document, we reproduce Schmid’s transcription in full here with a translation:

Frau Maria Anna Mozartin, Buchbinderin von Augspurg, lage in dermaßen gefährlicher hitziger Krankheit, daß man ihr alle Augenblück auf die Seel wartete, und die Sterb-Kerzen schon in die Hand gegeben hatte. In diesem höchst-tödtlichen Zustand verspricht die Dienstmagd, aus innerlichem Mitleyden bewegt, und weil die sterbende Frau gar nichts mehr um sich selbsten wußte, ja fast kein Lebens-Zeichen von sich gegeben, dise ihre in Zügen ligende Frau zu dem wunderthätigen Heil. Creutz, mit inniglicher Bitt um ihre Gesundheit, und Verlobung einer Wallfahrt. Und sihe! also gleich auf dises Versprechen kommt die Frau wieder zu sich selbsten, und über einige Zeit höret sie von der Magd, daß sie eine Wallfahrt zum Heil. Creutz für ihr Wiedergenesung versprochen habe, sie solle demnach anjetzo selbsten das Heil. Creutz inbrünstig anruffen, und da sie nun wieder bey ihrem Verstand, ihre Hofnung gleichfalls mit kräftigem Vertrauen dahin setzen, und das gemachte Gelübd auch für sich selbsten erneueren, damit, was Gott auf Anruffen des Heil. Creutz bereits angefangen, auch vollkommen machen, und ihr die vorige gänzliche Gesundheit verleyhen wolle. Die Frau folgt dem guten Rath ihrer getreuen Magd gar gern, verlobt sich neuerdingen hieher, wird von Stund zu Stund besser, kommt endlichen ganz frisch und gesund nach Biberbach, und samt der Magd danckt sie dem Heil. Creutz mit einer Votiv-Tafel und Erzehlung der erhaltenen Gnad. Anno 1758. [Schmid 1948, 154]

Frau Maria Anna Mozart, bookbinder in Augsburg, lay in such a dangerous fevered illness, that her soul was expected to depart at any moment, and the death candle had already been put in her hand. In this near-death state, her servant girl—moved by deepest compassion, and because the woman was no longer aware of herself, indeed, showed almost no signs of life—made a profound prayer to the miraculous Holy Cross for the woman in the throes of death and promised a pilgrimage. And lo! As soon as this promise was made, the woman came to herself again, and after a time heard from the girl of the promised pilgrimage to the Holy Cross for her recovery; that she should thus now herself fervently call upon the Holy Cross, and since she had now regained awareness, she should likewise place her hopes thereon with powerful faith, and herself renew the vow in order that what God had already begun upon the appeal to the Holy Cross should be fulfilled, and He would restore her to complete health. The woman followed the advice of her faithful girl, she renewed the vow, became better hour by hour, and finally came entirely fresh and healthy to Biberbach, and together with her girl she thanked the Holy Cross with a memorial plaque and the story of the blessing bestowed. Anno 1758.

(Schmid writes that Maria Anna Mozart’s “Votiv-Tafel” was discarded along with many others in the nineteenth century.)

Schmid’s argument for Biberbach as the location of the contest between Mozart and Bachmann is ingenious and persuasive. But oddly, he seems to have overlooked Christmann’s own correction in the Musikalische Korrespondenz on 19 May 1791, transcribed at the top of this page; Christmann explicitly names Biberbach as the location of the contest and even mentions the link with Bachmann’s grandfather. Nissen must have known of this correction: it is the simplest explanation for his garbled reference to “Biberach.” Christmann had very likely heard the story of the contest directly from Bachmann himself, who probably then saw the error in Christmann’s original article and sent him a correction (Bachmann lived until 1825). So we have little reason to doubt that the contest took place and that its location was the pilgrimage church in Biberbach. Christmann’s correction is not included in Dokumente or its supplements.

Because Christmann’s correction was overlooked, Schmid’s account in 1948 became the direct or indirect source for subsequent references to the contest. As is typical of Schmid’s work, he draws on a wide range of primary sources. But in this case, before even mentioning Christmann’s 1790 article on Bachmann, Schmid gives an extended, rather saccharine, and largely speculative description of the Mozarts’ stop in Biberbach and the contest between Wolfgang and Bachmann. In the course of this description, Schmid writes:

Vermutlich war es Christoph Moritz Bernhard, Reichsgraf Fugger von Kirchheim [sic] und Weißenhorn, Herr zu Boos, Reichau, Wellenburg und Marktbiberbach und k. k. wirklicher Kämmerer, der die Mozartschen Wunderkinder in der Dillinger Residenz gehört hatte und nun neugierig darauf war, wie sich daneben der musikbegabte Enkel seines Biberbacher Organisten ausnehmen würde. Schon in Dillingen wird er mit Vater Leopold die Rast in Markt Biberbach vereinbart haben, um die Mozartkinder mit dem schwäbischen Wunderkind zusammenzuführen, das um zwei Jahre älter war als der kleine Wolfgang. [...] Nicht unmöglich ist, daß bei diesem Plan und seiner Verwirklichung auch der ältere Bruder des Fuggergrafen, Anselm Joseph Viktorian, Reichsgraf Fugger von Kirchberg und Weißenhorn, regierender Herr der schwäbischen Majoratsherrschaft Babenhausen und Kettershausen, beteiligt war, der sich u. a. gleichfalls Herr zu Markt Biberbach nannte. Die beiden Brüder hatten die Herrschaften der beiden Linien “Jakob Fugger-Boos” und “Jakob Fugger-Babenhausen” teilweise in gemeinschaftlicher Verwaltung. Dazu gehörte auch unser Markt Biberbach, das den Fuggern seit Jahrhunderten als Lehen der vorderösterreichischen Markgrafschaft Burgau angehörte. [Schmid 1948, 150–51]

[translation:]

Presumably it was Christoph Moritz Bernhard, Imperial Count Fugger von Kirchheim [sic] und Weißenhorn, Herr zu Boos, Reichau, Wellenburg und Marktbiberbach und k. k. wirklicher Kämmerer, who had heard the Mozart wunderkinder in the Dillinger Residenz, and was now curious how the musically talented grandson of his Biberbach organist would compare to them. Already in Dillingen he will have arranged with father Leopold the stopover in Markt Biberbach, in order to bring the Mozart children together with the Swabian wunderkind, who was around two years older than little Wolfgang. [...] It is not impossible that the older brother of the Fugger count, Imperial Count Anselm Joseph Viktorian von Kirchberg und Weißenhorn, took part in this plan and its realization, as he held the title of, among other things, Herr zu Markt Biberbach. The two brothers had, in part, joint administration over the domains of the “Jakob Fugger-Boos” and “Jakob Fugger-Babenhausen” lines. To these belonged our Markt Biberbach, which had belonged to the Fuggers for centuries as a fiefdom of the Outer Austrian Margravate of Burgau.

This passage could be used in graduate seminars as an exemplar of the “speculative historical” mode, employing in the space of just a few sentences three of its favorite tropes: “vermutlich” (presumably), “schon in Dillingen wird er … vereinbart haben” (already in Dillingen he will have arranged …), and “nicht unmöglich ist, daß” (it is not impossible that). Yet it is from this paragraph that the name of Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard has become firmly associated in the Mozart literature with the organ contest in Biberbach. In his commentary to Christmann’s article on Bachmann (Dokumente, 333), Deutsch (citing Schmid) writes as if it were fact: “Bachmanns Patron war Graf Christoph Moritz Bernhard Fugger von Kirchheim und Weißenhorn” (Bachmann’s patron was Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard Fugger von Kirchheim und Weißenhorn). The speculation is repeated (with “wahrscheinlich” replacing Schmid’s “vermutlich”) in the commentary in Briefe to Leopold’s letter to Hagenauer of 10 Nov 1766:

Bevor die Mozarts “Augsburg” erreichten, etwa auf der Hälfte der Reiseweges zwischen Dillingen und Augsburg, fand (am 6. 11. 1766) in der Wallfahrtskirche Markt Biberbach (vgl. Schmid-Mb Abb. XVII) zwischen Wolfgang und dem damals zwölfjährigen Joseph Sigmund Eugen Bachmann (später Pater Sixtus Bachmann, zuletzt im Kloster Obermarchthal an der Donau) ein Wettspiel auf der Orgel statt, wahrscheinlich auf Veranlassung von Christoph Moritz Bernhard Reichsgraf Fugger von Kirchheim und Weißenhorn, k. k. wirklicher Kämmerer, der Wolfgang und Nannerl in Dillingen gehört haben mag. Vgl. NissenB S. 120; SchmidMb S. 148 ff. [Briefe, v:167–68]

Before the Mozarts reached “Augsburg,” at about half of the distance between Dillingen and Augsburg, a contest on the organ took place (on 6 Nov 1766) between Wolfgang and the 12-year-old Joseph Sigmund Eugen Bachmann (later Father Sixtus Bachmann, lastly in the abbey in Obermarchthal an der Donau), in the pilgrimage church of Markt Biberbach (cf. Schmid 1948, plate 17), probably at the instigation of Imperial Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard Fugger von Kirchheim und Weißenhorn, k. k. wirklicher Kämmerer, who may have heard Wolfgang and Nannerl in Dillingen (cf. Nissen 1828, 120; Schmid 1948, 148ff).

More recently, the count’s alleged involvement has again been elevated to fact in the title of an article: “Graf Christoph Moritz Bernhard Fugger von Kirchberg-Weißenhorn und der Biberbacher Orgelwettstreit” (Loerke, 2010).

Given the frequent references to him, it may come as a surprise that (to our knowledge) there is no known primary evidence whatsoever to suggest that Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard was in Dillingen when the Mozarts were there, that he was Bachmann’s patron, or that he had anything to do with the event in Biberbach. Schmid’s additional minor errors in referring to the Fuggers and their domains have muddied the waters even further.

Admittedly, the genealogy of the many Fugger lines and the history of their scattered lands is complicated and confusing. For our purposes, the most useful and accessible guide is the 1771 edition of Des Hochlöbl. Schwäbischen Crayses vollständiges Staats= und Addreß=Buch, a guide to Swabian nobility and their administrative staffs. Schmid himself relied on several volumes from this series, although not this particular one (see esp. Schmid 1948, 422–23, note 393). The 1771 edition is close enough in time to the contest in 1766 that no changes to relevant lines of the family or their domains had taken place in the interim, but relatively recent changes are still explained.

The Fuggers are covered on pages 145–62 of the Addreß=Buch, with the lines and branches of the family clearly distinguished by outline-style numbering and differing font sizes. We can see here that the Fugger nobility consisted of two main lines: the “Raymund=Linie” and the “Anton=Linie”, descending respectively from Raymund Fugger (1489–1535) and Anton Fugger (1493–1560), sons of Georg Fugger. The brothers Raymund and Anton inherited the wealth of their uncle Jakob Fugger “der Reiche” (the Rich, 1459–1525), who had no direct male heir. In 1507 Jakob had purchased from King (later Emperor) Maximilian I many of the territories that became the core of the Fugger family’s holdings, including Kirchberg and Weißenhorn; and crucially for our story, in 1514 he purchased from the Marschällen von Pappenheim the domain of Markt Biberbach. (For a clear and concise guide to the early history of the Fugger domains, see Immler 2015.) In 1535, King (later Emperor) Ferdinand I bestowed upon Raymund and Anton the right to the hereditary title Count of Kirchberg und Weißenhorn. (Schmid’s erroneous “Kirchheim und Weißenhorn” for \ Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard is all the more confusing because there was, in fact, also a distinct “Kirchheim” branch of one of the Fugger lines.)

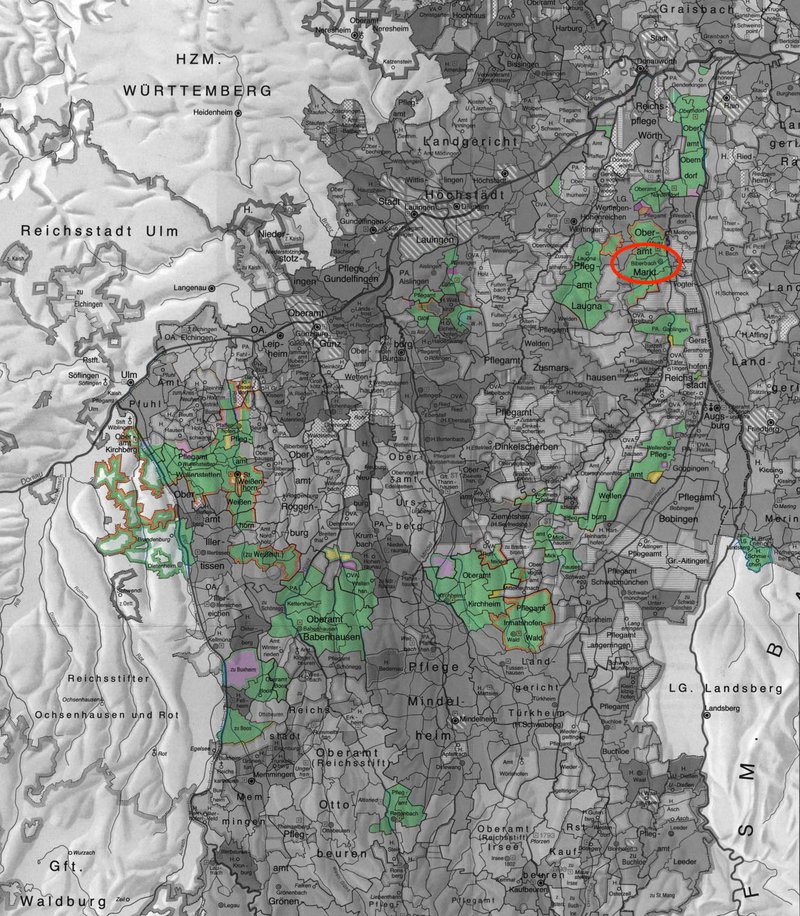

A map of the Fugger domains in 1802 (Biberbach circled in red)

(Historisches Lexikon Bayerns)

Raymund’s line subdivided into the Pfirtisch line (which itself had three branches) and the Kirchberg-Weißenhorn line; the latter designation is also a potential source of confusion, because many members of other lines and branches of the Fugger family who did not belong to the Kirchberg-Weißenhorn line were nevertheless referred to as “Graf von Kirchberg und Weißenhorn,” apparently because that was the root title for the entire family, stretching back to 1535.

Anton Fugger’s line was subdivided into three lines named after his sons: Marx (or Markus), Hans (Johannes), and Jakob. (It was one of the three branches of the Hans line that carried the designation “Kirchheim.”) Jakob Fugger’s offshoot of Anton’s line was further subdivided into three branches, which the 1771 directory designates as “Jac[ob=]Fugger=Babenhausen”, “Jacob=Fugger=Booß,” and “Jacob=Fugger=Wasser oder Wöllenburg.”

The head of the Fugger-Babenhausen branch was (to give his name as it appears in the Addreß=Buch, 156): “Herr Anselm Victorian Joseph Raymund, Joh. Nepom. des H. R. R. Graf Fugger von Kirchberg u. Weissenhorn.” Count Anselm had become head of the Fugger-Babenhausen branch upon the death of his father, Count Johann Jacob Alexander Sigmund Rudolph, on 23 Apr 1759. Count Anselm, born in 1729, was in fact only the fourth oldest living son; but his three older brothers were already in the church by the time of their father’s death: Maximilian Joseph Anton (b. 1721) had been in the abbey of Kempten since 1743; Wilibald Maria Felix (b. 1724) was a member of the Johanniterorden; and Rupert Joseph Johann Nepomuk (b. 1726) had become a Jesuit in 1745 (see the Addreß=Buch 1771, 157). As Count Anselm was not in the church, it fell to him to become head of the Fugger-Babenhausen branch of the family and administrator of its holdings. Bachmann’s birthplace, Kettershausen, was within the Fugger-Babenhausen domain, but Markt Biberbach was not, and it is certain that Christmann was referring to Count Anselm as Bachmann’s early patron.

Until 1764, Markt Biberbach was in the domain of the third branch of the line descending from Anton Fugger’s son Jakob, the “Jacob=Fugger=Wasser= oder Wöllenburg” branch. According to the Addreß=Buch of 1771, the head of this line had been:

(BSB)

Weyl. Se. Hochgräfl. Excell. der Hochgebohrne Herr, Herr

Joseph Maria, des H. R. R. Graf Fugger von Kirchb.

und Weissenhorn, regier. Herr zu Wasserburg, Wöllenb.

Röttenbach, Gablingen, Marktbiberbach, Welden und Irr=

mannshofen obm Wald, Churbayer. wirkl. Camm. u. Com-

mand. des St. Georgii Ritter=Ord. geb. 25. Jul. 1714. †

21. Jul. 1764. [Addreß-Buch 1771, 159]

“Marktbiberbach” is explicitly listed here as among the domains of the late Count Joseph Maria. The Addreß=Buch appends an explanatory note on the disposition of his domain after he died without issue:

(BSB)

Nota. Weilen keine Descendenz vorhanden, seynd die be=

sessene Herrschaften. excl. Wasserburg und Welden, an

die beede vorstehende Herren Reichs=Grafen und Gebrü=

dere, Fugger zu Babenhausen und Booß gefallen, und

werden dermalen gemeinschaftlich administrirt.

[Addreß-Buch 1771, 160]

Note. Because there were no descendants, the domains

in his possession, exclusive of Wasserburg and Welden, fell

to the two foregoing Herren, Imperial Counts and brothers,

Fugger zu Babenhausen and Booß, and they are at present

jointly administered.

The first of the “foregoing” brothers was Count Anselm. The other was his younger brother Count Christoph Moritz Bernhard Wunibald Johann Nepomuk (b. 1733), who was head of the “Jacob=Fugger=Booß” branch of the family. Thus in 1766 Markt Biberbach was under the joint administration of these two brothers. But even though Markt Biberbach was indeed part of their joint domain at the time of the encounter between Mozart and Bachmann, there is (pace Schmid and those who have cited him), no known evidence that either of them ever heard Mozart play or had anything to do with arranging the contest.

The organ on which the contest took place had been completed by 1694, and is said to have been built by David Jakob Weidner (see Kluger 2016, 59); Schmid writes that it was dismantled in 1888 (on this organ, see Schmid 1948, 150, 153, and 423n396; Schmid writes that the builder is unknown).

At the end of his 1790 article on Bachmann, Christmann writes that Bachmann “komponierte Gleims anakreontische Lieder” (composed Gleim’s anacreontic songs). The reference is to the poet Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim (1719–1803), author of “Ich möchte wohl der Kaiser sein!” (first printed 1776), set by Mozart in 1788 as Ein deutsches Kriegslied (K. 539). Gleim’s poems were set by a wide range of composers, including C. P. E. Bach, Reinicke, Rosetti, Schulz, Sterkel, Stephan, Zelter, Loewe, Haydn (“Hin ist alle meine Kraft!”, “Ich bin vergnügt, will ich was mehr?” = Zufriedenheit), Beethoven (Selbstgespräch, WoO 114), Naumann, Benda, Zumsteeg, and later by Hindemith and Berg. Gleim published two collections of songs with “Anakreon” in the title: Lieder nach dem Anakreon (1766) and Neue Lieder. Von dem Verfasser der Lieder nach dem Anakreon (1767). It is possible that Christmann meant to refer to one of these; but “anacreontic” is a generic term for poems in the style of the ancient Greek poet Anacreon, often celebrating love and wine, and could also refer to a wider range of Gleim’s poems. In any case, Christmann’s correction of 1791, which probably stemmed from Bachmann himself, specifies that Bachmann was not the composer of anacreontic songs by Gleim.