Commentary

(pdf)The first part of this report, on performances of C. P. E. Bach’s Die Auferstehung und Himmelfahrt Jesu, is an abridged quotation from a well-known account in the Hamburger Correspondent, found in slightly different form in Forkel’s Musikalischer Almanach (Dokumente, 273; Forkel gives the date of the second performance as 4 Mar, not 2 Mar). However the second part of the report, on Handel’s Judas Maccabeus, is previously unknown, and gives welcome information about the otherwise poorly documented private concert life of the Viennese nobility. The Auszug gives the source of this part as “Orig[inal] Nach[richt]”; it is thus a rare original item in a newspaper that mostly limited itself to extracts from other papers. As usual the report is unsigned, but it may be the work of Karl Franz Guolfinger Ritter von Steinsberg, the Auszug’s editor (see the entry for 12 Jan 1788). Mozart is already known to have conducted the performances of Die Auferstehung, but this report, together with a previously undescribed printed libretto, seems to suggest that he conducted Handel’s Judas Maccabeus in 1788 as well.

Both the Bach and Handel performances appear to have been associated with an informal association of noble musical patrons who sponsored performances of major choral works. Known now as the Gesellschaft der Associierten Cavaliere (or Cavaliers), the association is best-known for its role in the genesis of Haydn’s late oratorios, but it had a history extending more than a decade before this. Because the association’s concerts were “private” (that is, with attendance by invitation only), little information about them survives, and details need to be pieced together from a variety of sources. The existing scholarship on the association is in need of revision (even the standard form of the association’s name, Gesellschaft der Associierten Cavaliere, is not attested before the twentieth century), but this commentary will be limited to considering the association’s early history and Mozart’s first involvement.

Just when the association began its practice of mounting concerts is not clear. As is well-known, the driving force behind its activities was Baron Gottfried van Swieten, and it may be presumed that the common sponsorship of concerts did not commence before his return to Vienna in 1777. According to a newspaper article by Anton Mörath, former archivist to the Schwarzenberg family, the “Associirten” began their activities in 1780, and from 1783 to 1797 they sponsored performances of Handel oratorios (Mörath 1901, 2). Mörath did not give his source, but perhaps he founded his statement on documentary evidence in the Schwarzenberg archives; both Prince Johann and his son Prince Joseph zu Schwarzenberg were members of the association. Given the informal nature of the Gesellschaft, the idea of a single “start date” may be misconceived, and perhaps it is more likely that a variable number of noble families began contributing before the tradition coalesced into an identifiable “association” with standard expectations of its members.

The precise repertoire in the first half of the 1780s is unknown, but there are a few references to choral performances in Vienna that cannot be matched to known public concerts and could conceivably be associated with the Gesellschaft. The colourful Ignaz Aurelius Fessler, who lived in Vienna from 1782 until 1784, recalled in his memoirs attending “musikalischen Gesellschaften” at this time featuring Handel’s Messiah, Pergolesi’s Stabat mater and Bach’s Salve regina (presumably J. C. Bach’s settings W.E23 or E24; Fessler 1851, 110). Schönfeld’s Jahrbuch reports performances given by Graf Franz Esterhazy of Handel choruses, C. P. E. Bach’s Heilig H 778 and Pergolesi’s Stabat mater, although these probably took place a few years later (Schönfeld 1796, 70).

From the wording of the report in the Auszug, it seems that the two performances of Judas Maccabeus took place at the palace of Graf Johann Baptist Esterhazy in reasonably close proximity to the performances of Die Auferstehung (on the identification of “Graf Johann Esterhazy” as Johann Baptist, see Landon 1989, 116-19). Judas Maccabeus, in a German translation by Johann Joachim Eschenburg (not van Swieten), had received its first reasonably complete performances in Vienna at the Lent 1779 academies of the Tonkünstler-Societät. Those performances featured “additional accompaniments” that were at least in part the work of Joseph Starzer, although there was a nineteenth-century tradition that attributed a Judas arrangement to Mozart (see Holschneider 1961; there is no reason to support the resurrection of this tradition in Cowgill 2002). In 1834, Leopold von Sonnleithner interviewed Joseph Weigl during his investigations into the authorship of the Judas arrangement, and reported the conversation as follows (Sonnleithner 1836, 247-48; see also NMA X/28/1/1, KB p. 15):

[Weigl] besitze eine alte Abschrift jener Partitur, nach welcher dieses Werk bei Baron van Swieten, und später von der hiesigen Tonkünstler-Wittwengesellschaft, aufgeführt worden war…Weigl erzählte mir hiebei, dass er selbst in den Concerten bei van Swieten gewöhnlich die Recitative am Claviere begleitet habe, – dass der Hoftheatercomponist Starzer, noch ehe Mozart an diesen Conzerten persönlich Theil nahm, für dieselben Händels Judas Maccabäus bearbeitet, und dessen Aufführung selbst geleitet habe, – dass Mozart durch den guten Erfolg dieser Bearbeitung auf den Gedanken gebracht worden sei, auch seinerseits Werke Händels nach Starzers Art zu instrumentiren, niemal aber das Oratorium Judas Maccabäus bearbeitet habe, wozu auch gar kein Anlass vorhanden war.

Weigl’s reported testimony is consistent with his two autobiographies (edition in Angermüller 1971), in which he described his participation in the famous Sunday run-throughs of “old music” at van Swieten’s. He continued to assist with van Swieten’s musical activities in the hopes of a securing a stipend from the Baron, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

Both the Auszug and Weigl are silent on precisely when van Swieten’s performances of Judas Maccabeus took place. The performances presumably did not take place any earlier than 1785, as it was in that year that Paul Wranitzky (1756–1808), the subject of the Auszug’s fulsome praise, is said to have become director of music to Graf Esterhazy. Indeed, one encounters numerous references in the literature to performances of the oratorio in 1786. The origin of these alleged performances seems to be a series of articles by Reinhold Bernhardt, who made the first systematic attempt in the 1920s and 1930s to document the life of van Swieten and the Gesellschaft. Bernhardt presented a list of works that “scheinen von 1786–1792...aufgeführt worden zu sein”, including Judas Maccabeus in 1786 and Hasse’s La conversione di S. Agostino in 1787 (Bernhardt 1930a, 148–49). Bernhardt provided more detail in another article published the same year: “Die Konzerte setzten im Herbst 1786 mit der Aufführung des Judas Maccabäus ein; Bearbeitung und Direktion waren Starzer übertragen, am Cembalo saß Mozart” (Bernhardt 1930b, 436). Unfortunately, Bernhardt gave no source for these Handel and Hasse performances in 1786–87 beyond “spärliche Berichte…zu meist in Tagebüchern”, and we have been unable to identify Bernhardt’s sources independently; there is no reference, for example, in Count Zinzendorf’s diaries.

While there is nothing inherently implausible about these alleged performances, some doubt must remain given Bernhardt’s apparent habit of making unwarranted inferences from his source material. For example, he lists an otherwise unknown performance of Mozart’s Requiem during Lent 1792 (Bernhardt 1935, 541, 543), probably by reference to Joseph Eybler’s obligation to complete the work “by the middle of the coming Lent” (Dokumente, 375). It is even possible that Bernhardt confused the alleged Hasse performance with a performance of S. Agostino which definitely took place in Berlin in 1787. Regardless, the unquestioning acceptance of Bernhardt’s information in the recent literature (see for example NMA X/28/3–5/2, xiii) and even more the presumption that the Gesellschaft der Associierten Cavaliere began its activities in 1786, is not justified by the evidence.

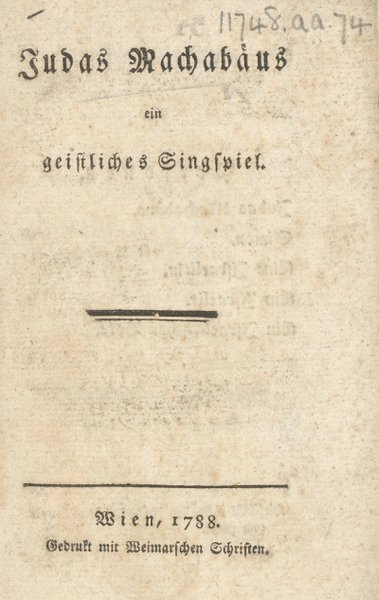

Mozart’s first definite involvement with the Gesellschaft occurred with the C. P. E. Bach performances described in this article (there was a further public performance at the Burgtheater on 7 Mar 1788). As well as conducting the performances, Mozart was responsible for at least some of the changes made to the brass and woodwind parts (K. 537d) to accommodate Viennese practice (see Holschneider 1970 and NMA X/28/3–5/2). It seems to have escaped general notice, however, that two Viennese libretti survive in the British Library for Die Auferstehung and Judas Maccabeus, both dated 1788 (GB-Lbl, 11748.aa.73 and 11748.aa.74; we are grateful to Rupert Ridgewell for his assistance with these sources).

Libretti for Die Auferstehung and Judas Machabäus, printed by Johann Martin Weimar (Vienna, 1788).

Both libretti were unknown to Holschneider and the NMA (Smither 1987, 346n63, mentions the Auferstehung libretto). The Judas libretto appears to confirm that Judas Maccabeus was in fact performed in Vienna in 1788 (Rackwitz 2002, 258, lists such a performance, without giving a source). Unfortunately, the libretto gives no indication of when exactly the oratorio received its two performances, nor is there any indication of the identity of the soloists. Based on their appearances in Die Auferstehung, we may speculate that Valentin Adamberger appeared as Judas, Ignaz Saal as Simon, and Aloysia Lange as Eine Israelitin, although there are of course other possibilities.

Like the TKS performance of 1779, the libretto uses Eschenburg's German translation with substantial cuts: in Part I, the sequence from the recitative “To Heav’ns Almighty” to the duet “Come, ever smiling Liberty”, the chorus “Disdainful of danger,” and the recitative/aria “Ambition! if e’er honour was thine aim…No, no unhallow’d desire” were omitted. In Part II, the recitative/arias “Victorious Hero!...So rapid thy course is” and “Enough: To heav’n…With pious hearts" together with the duet “Oh! never bow we down” were cut. In Part III, the opening aria “Father of Heav’n!” and the recitative/aria “O grant it, Heav’n…So shall the lute” were omitted. In contrast, the Die Auferstehung libretto, which is similarly uninformative about the circumstances of its performances, shows that the cantata was performed complete, as the surviving performance material also confirms.

Given the proximity of the performances, is it possible that Mozart took part in Judas Maccabeus in early 1788 as well? According to Weigl, Starzer had directed (geleitet) a performance of Judas in his own arrangement “even before Mozart took part personally” in the van Swieten concerts; this might refer to the 1779 performance by the Tonkünstler-Societät or the mysterious performance of 1786. Starzer cannot have participated in the 1788 performance, however, as he had died on 22 April 1787. Sonnleithner, basing himself on “die glaubwürdigsten Zeitgenossen” (presumably Weigl), later wrote that Mozart took over the direction of the van Swieten concerts after Starzer’s death (Sonnleithner 1846, 94), and Mozart was indeed regularly involved with van Swieten’s concerts at least from 1788.

Taken together, then, these reports suggest that it was Mozart (or perhaps Weigl) who directed the Judas performances from the keyboard in early 1788 at the residence of Graf Esterhazy, with Wranitzky leading the orchestra. This residence was probably located in the palace owned by Esterhazy’s brother-in-law Karl IV. Palffy von Erdödy (Stadt 52, not to be confused with the main Palffy palace on Josephplatz). The palace is no longer extant, but was located at approximately Schenkenstraße 12 (not 17, as given in Dokumente, 273). According to the Steuerfassion of 1787–88, Esterhazy and his wife Maria Anna lived on the second floor of the palace, where they had 17 rooms at their disposal (A-Wsa, Steuerfassion B34/1, f. 61; this entry was located by Michael Lorenz, to whom we are very grateful). Given the size of the ensemble and the audience, presumably the Judas performance took place in a ballroom or the central courtyard.

The Palffy Palace (Stadt 52), in the 1785 edition of Joseph Huber’s view of Vienna.

The suggestion that Mozart conducted a performance of Judas in 1788 fits neatly with a sketchleaf (Skb 1788a) that contains material dating probably from the same time (see Bernhardt 1935, 537, Woodfield 2006, 33 and Black 2007, 403-404). At the top of the page is the beginning of the famous chorus “See, the conqu’ring hero comes” from Judas Maccabeus, apparently in an intended arrangement for chorus and keyboard. This is not in Mozart’s hand, but in the hand of his student Franz Jakob Freystädtler. (Bernhardt mentioned another Mozart autograph apparently quoting this theme, but this is actually Mozart’s copy [K. 562b] of Michael Haydn’s canon “Adam hat sieben Söhn” MH 699; we are grateful to Neal Zaslaw for this identification and see Arthur 2018, 102).

Entry by Freystädtler in Mozart’s sketchleaf Skb 1788a. A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 17559, f. 14v (detail).

The violinist and composer Paul Wranitzky had arrived in Vienna in about 1776, and by the time of the 1788 Judas had established himself as one of the leading musicians in the city. Wranitzky had been music director for Esterhazy since the mid-1780s (Lewis 1872, 198; Schuler 2001, 299), and in 1785 became leader of the orchestra at the Kärtnerthortheater, moving to the Burgtheater orchestra in 1787 when the Singspiel company disbanded.

Wranitzky may have been involved with the performances of Mozart’s later arrangements of Acis und Galatea K. 566 (Nov 1788), Der Messias K. 572 (Feb-Mar 1789), and Das Alexander-Fest K. 591 and Ode auf St. Caecilia K. 592 (Jul 1790). The second copy of the first violin part in the original performance material for Acis has “Wran[itzky]” written on the cover (NMA KB, 13) and the same part in the original material for Caecilia has “Wrz” (NMA KB, 7), although it is uncertain whether this refers to Paul or his brother Anton. No surviving performance material for the 1788 Judas has been identified, although the sources require further investigation (A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 13046, for example). The Gesellschaft performed Judas Maccabeus again on 15 Apr 1794 (Morrow 1989, 387), for which another libretto was printed.

This report in the Aufzug offers new information about Viennese concert life, Mozart’s activities as a conductor, and his knowledge of Handel (see also Black 2015). Mozart’s last engagement with Handel took place in Sep 1791, when he apparently conducted at least part of a concert in Prague featuring excerpts of Handel’s music, in connection with the coronation celebrations for Leopold II (Brauneis 2010, 248–50).